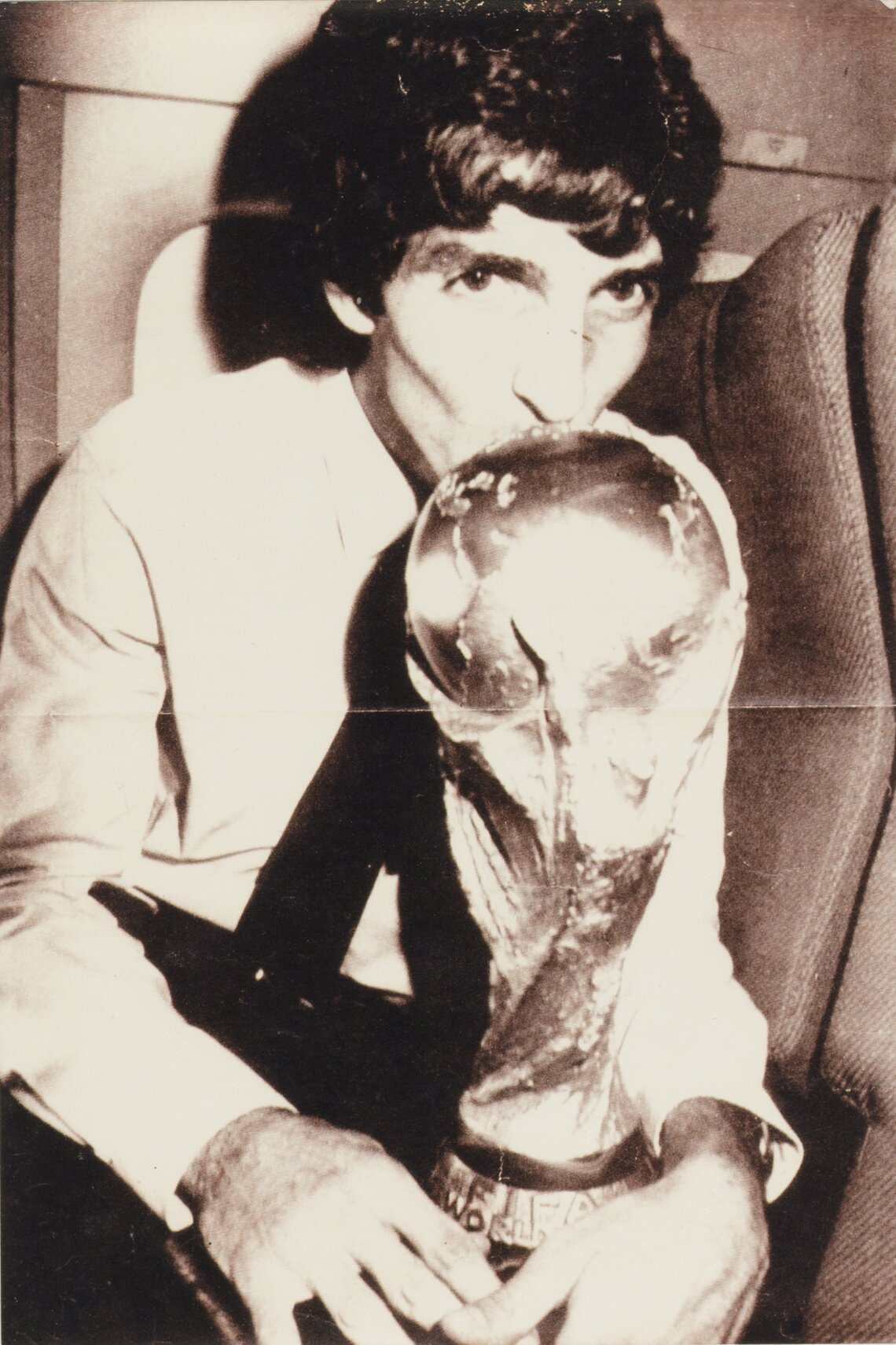

Many years later, standing before Valdir Peres and playing against Brazil in Barcelona’s Sarrìa Stadium, Paolo Rossi would remember those distant afternoons when his father would take him on a Vespa to watch Fiorentina from the Fiesole curve. Back then, Prato was a small town of textile artisans, built on the banks of a river that, in ancient times, had served the dyers who made the red jackets for Garibaldi’s men and the “blue cloth” for the royal troops. For him, playing football was such an overwhelming desire that, whenever he wanted to play, he would simply point at the ball with his finger.

1982 is the year Gabriel Garcia Marquez won the Nobel Prize.

1982 is the year Paolo Rossi won the World Cup.

What is this magical realism? Or at least, what does this moment mean to us Europeans, when history and dreams intertwine in a way that makes them indistinguishable? Alessandro Baricco explains it, describing why, paradoxically, Colombians themselves don’t understand what we call magical realism, because for them, that concept is just the way things are. “It’s because we’re poor and live in a complicated land,” a poet from those parts once told me. “So news doesn’t travel, knowledge crumbles, and everything is handed down in the only form that knows no obstacles and costs nothing: storytelling.” Then, with a certain logic, he told me this true story (though “true,” you understand, is a rather elusive word in those parts). A town on the coast, for its big festival, hires a circus from the capital. The circus boards a ship and sets sail for the town. Not far from the coast, however, the ship sinks: the entire circus goes down, and the currents carry it away. Two days later, in a nearby town (though “nearby” there doesn’t mean much, because if there’s no road cutting through the jungle, you could be a thousand kilometers away), fishermen go out in the evening to haul in their nets. They know nothing of the other town, nothing of the circus, nothing of the shipwreck. They pull up their nets and find a lion inside. They don’t bat an eye. They go home. “How did it go today?” the family must have asked the fisherman as they sat around the dinner table. “Oh, nothing much, today we caught lions.” We call this magical realism. You can see why they don’t get it.

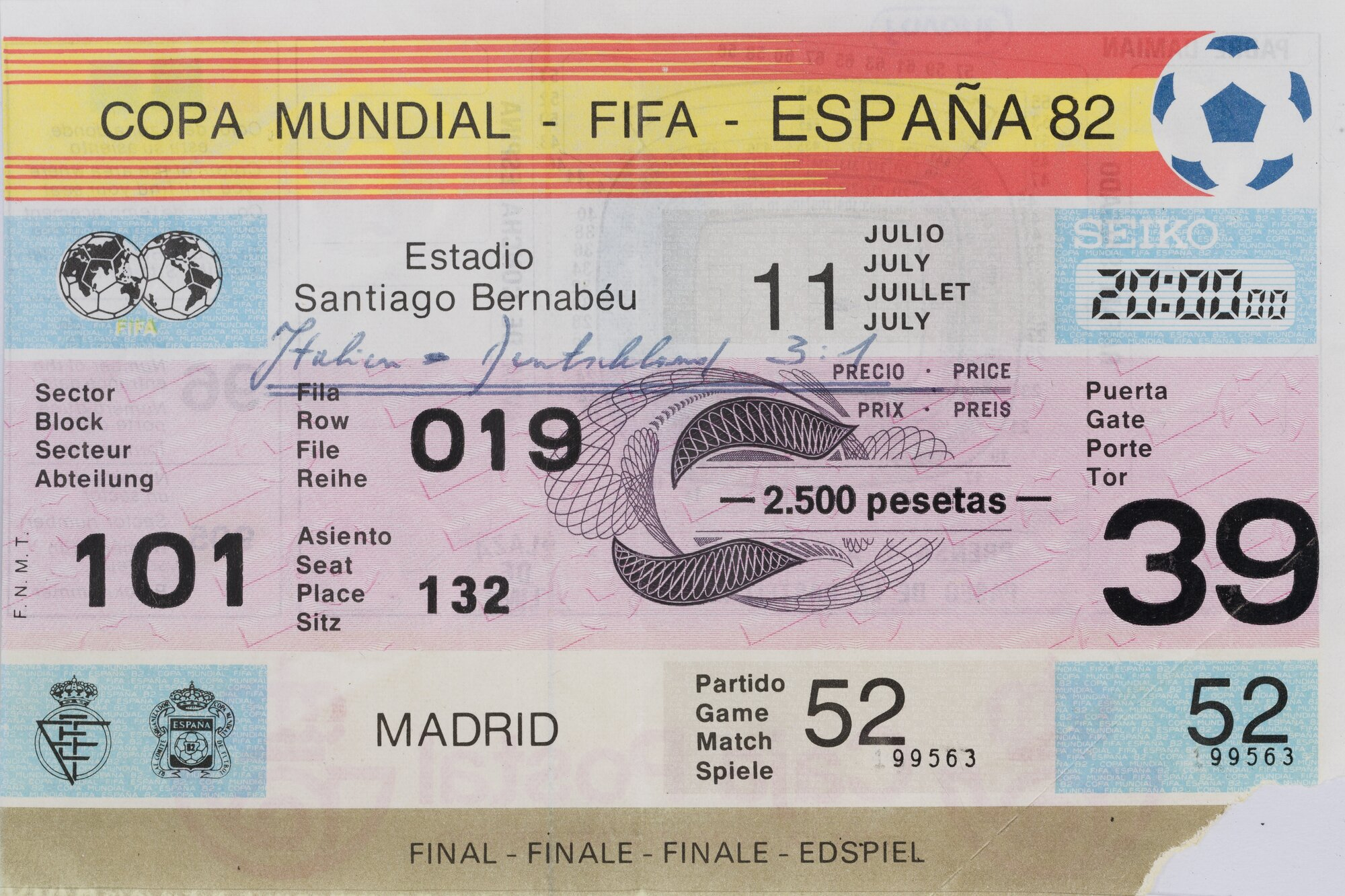

In 1982, Enzo Bearzot’s national team returned to Italy with nets full not of lions, but of footballs. Of the twelve goals scored, six- the most important ones—were netted by Paolo Rossi, or rather, paolorossi carrying Italy to World Cup victory and gifting the country its first boundless collective joy, closing the chapter on the horrors of the “Years of Lead.” Yes, sociologists say that period of pain, death, and massacres ended in the summer of 1982. It’s beautiful to think that a decisive contribution to ending the darkest era in Italy’s postwar history came from paolorossi, a gentle, slight young man who, in his own way, had also learned to endure suffering

Gabrielgarciamarquez and paolorossi are magical realism brought to literature and sport. They are a blessing, a gift to the world expressed through two forms of art. Blessed are the Colombians for having Gabo, and blessed are we for having Pablito. Thanks to them, literature and football have been a balm for our souls.

After all «things have a life of their own, it’s just a matter of waking up their souls,» as Gabriel Garcia Marquez writes in the Macondo of his One Hundred Years of Solitude, and as Paolo Rossi managed to do on the football fields of Spain during those six unforgettable days in July 1982.

1982

BY EUGENIO CARENA

It will be the wind,

a warm caress of indiscreet veil

that carries my smile to you

as I turn and look at you

my fragility shattered by victory

in those moments that precede history

a skinny child with uncertain steps

who becomes the indelible sign

of my gentle play

as I accept the challenge

the endless sun-drenched days

the rain that scolds me

in a friendly thunder that doesn’t frighten me,

life carries me far away on a carousel ride

from city to city until I become a man.

Falling, wounded in the fading joy

rising again, dazed by too much bitterness

believing once more until I’m sick of it

until I come back to life, to being myself

and you will hear my name

shake a blue cloth sky

rippled with crystals of salt

a constellation of pride

exploding in a chorus

all the love we needed

the night that falls gives, never enough,

the immortal breath of the gesture

that fulfills our waiting and

never confuses by remaining forever.