THE HEART INSIDE THE SHOES

Hearing them from the rectory window, they sounded like spring. Maybe it was because, like swallows or bees once did, they too would swarm outside as soon as they caught a whiff of the mild season. Not that rain ever really stopped them—in those cases, it was more the parents, especially the mothers, since they were the ones who had to scrub the mud off the pants.

They would run home after school, the strap of their satchel almost cutting into their necks from the eagerness to get there. They’d drop their morning things and rush out again, straight to the edge of that soccer field that only they could see. In the background stood Don Sandro’s rectory, all around the olive trees waiting to be pruned.

On the imaginary sideline, the swarming boys would stop, obedient to rules they’d set just once, and the two quickest would pick the teams. No uniforms available—the teams were divided between those who wore their shirts right side out and those who turned them inside out.

From the rectory window, Don Sandro enjoyed the spectacle of this announcement of spring. The first two kids to be picked for the team would run off to fetch two stones each, two big rocks, and once placed just right, they became the goalposts of a proper goal — complete with a crossbar and net.

After the first few games, when no one had taken him seriously, Paolo the scrawny one—Paolo with his skinny legs, quick as a cricket’s—was always among the first to be chosen. He’d earned their trust, and then their admiration, with goals, goals, and more goals.

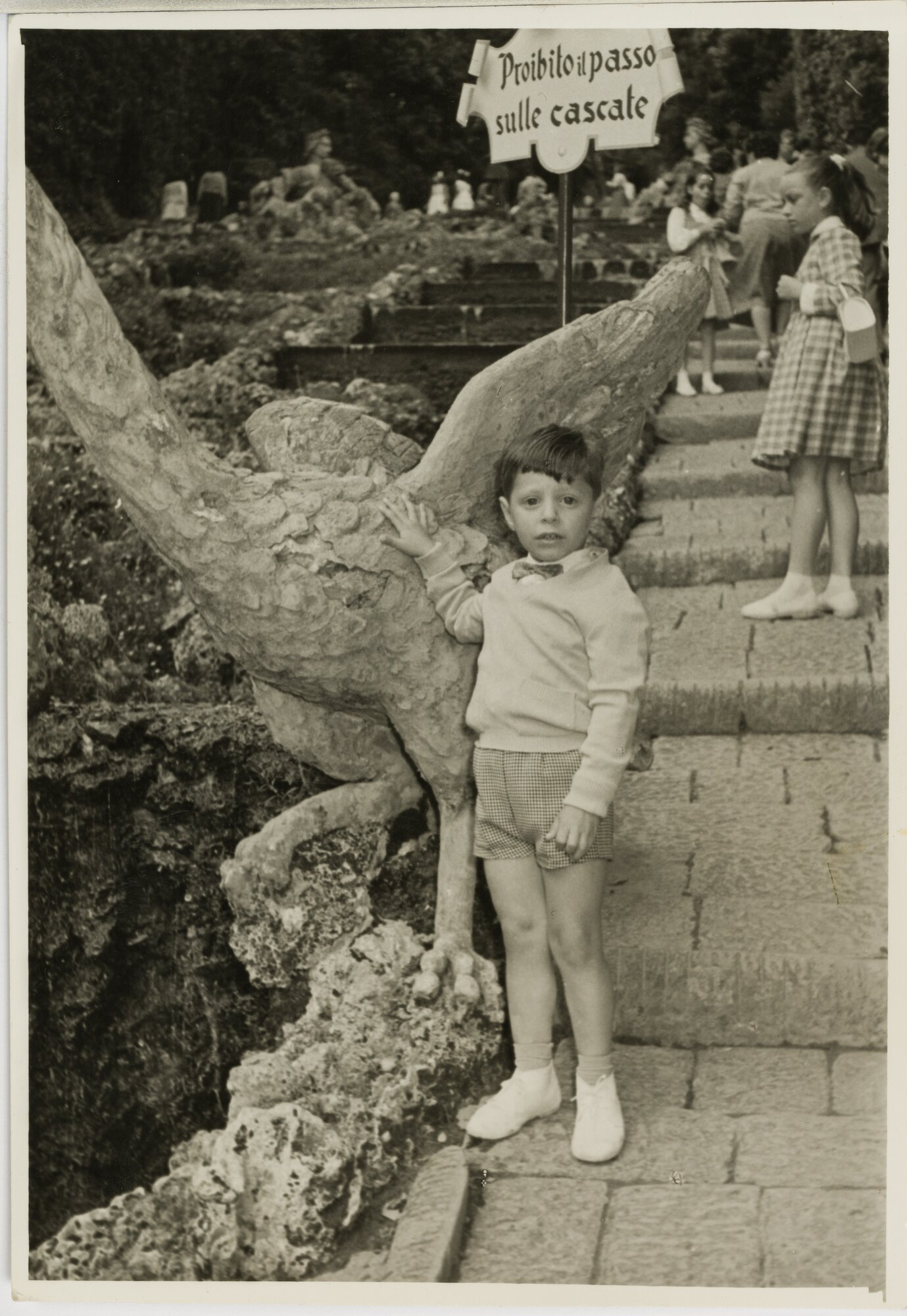

Paolo—actually, Paolino, because he really was tiny—played soccer in white tailor-made shorts and undershirt. Not because the family could afford custom clothes—quite the opposite—but because his mother, a seamstress by trade, knew how to make the most of her skills and leftover fabric. The Rossi brothers’ clothes were always impeccable, if not for that ring of churned-up earth and sweat that caked on every time they saw a ball.

If clothes weren’t much of a problem, shoes certainly were. Those, Mama Amalia couldn’t make, and so they had to be accounted for entirely in the family budget. With Paolo around, shoes ended up on the shopping list far too often, because that boy really put in the miles—oh, did he ever! Running, dribbling, weaving, juggling, feinting, sliding… It was enough to give a pair of Paolino’s shoes a nervous breakdown.

His father Vittorio—an accountant by trade and a sports enthusiast by passion, all sports, from cycling to soccer—would take Paolo on the Vespa every Sunday, from Prato to Florence, to watch Fiorentina play. Paolino, hair tousled by the wind and little hands clinging to his father’s waist, was small in age and stature, but big in dreams. On the ride from home to the stadium, he imagined the secrets of the champions, pictured himself in a locker room full of talent lacing up real soccer boots, wondered what it would feel like to walk out of the tunnel onto the field, dreamed of deciding important matches, and asked himself if the blue jersey of the national team would ever be within his reach. Dreaming big seems to cost nothing, but it isn’t so. If a dream bursts the bubble of the impossible to take root in the possible, you have to meet its demands—and Paolo did. Not even ten years old, he was already living like a professional footballer: healthy eating, as much training as possible, and early to bed. An adult’s life that didn’t weigh on him—in fact, it was the only way for him. Looking back, you’d call it “the way of champions.”

Papa Vittorio was an accomplice in this passion. Not only did he take his son to the stadium to witness the marvels of Kurt Hamrin, but he had glimpsed his son’s potential and kept a notebook where he recorded, match by match, everything Paolino did on the field—from goals to plays, even the kicks he took from opponents trying to keep him in check.

Vittorio also paid great attention to the care of the family’s shoes: he cleaned and polished them with stubborn dedication because, he said, “well-kept shoes are always a good calling card,”, but above all because shoes, to him, were “the soul of a person.”And one evening, faced with yet another pair of football boots destroyed in less than a month, Paolo’s calling card was hardly honorable, and as for his soul—well, who knew where it had gone off to hide. Confronted with this disaster, Mama Amelia imposed an exemplary punishment: a week without the parish, a week without running wild among the olive trees, a week without soccer.

A week without goals. It was a punishment that the boy, in love with football, remembered even half a century later: a week without setting foot on the field! Fate would keep him off the pitch at other, far more painful times, but he knew that’s where he belonged, with his heart inside his shoes, running faster than the wind.