Hello Paolorossi,

My name is Fabrício de Souza. I was born on July 5, 1982, in Imbituba—a town of 40,000 souls in the state of Santa Catarina, southern Brazil. used to be a footballer; I started out at the Zico Football Center, right there in Imbituba. I had a good career, you know? I won a Brazilian championship with Corinthians, then played for Cruzeiro and São Paulo, but what I really can’t forget are those three matches when I wore the green-and-gold jersey of the Under-23 National Team.

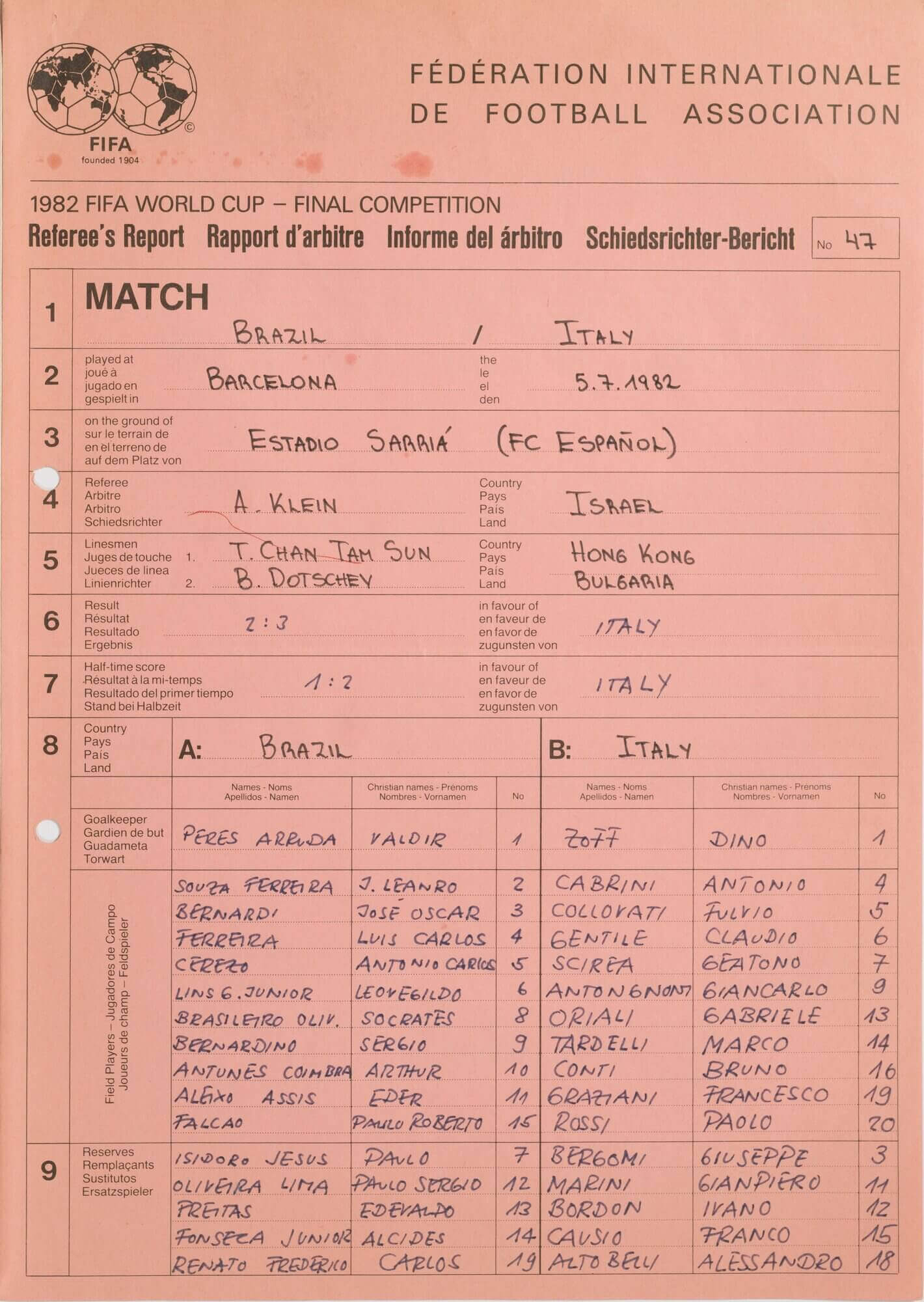

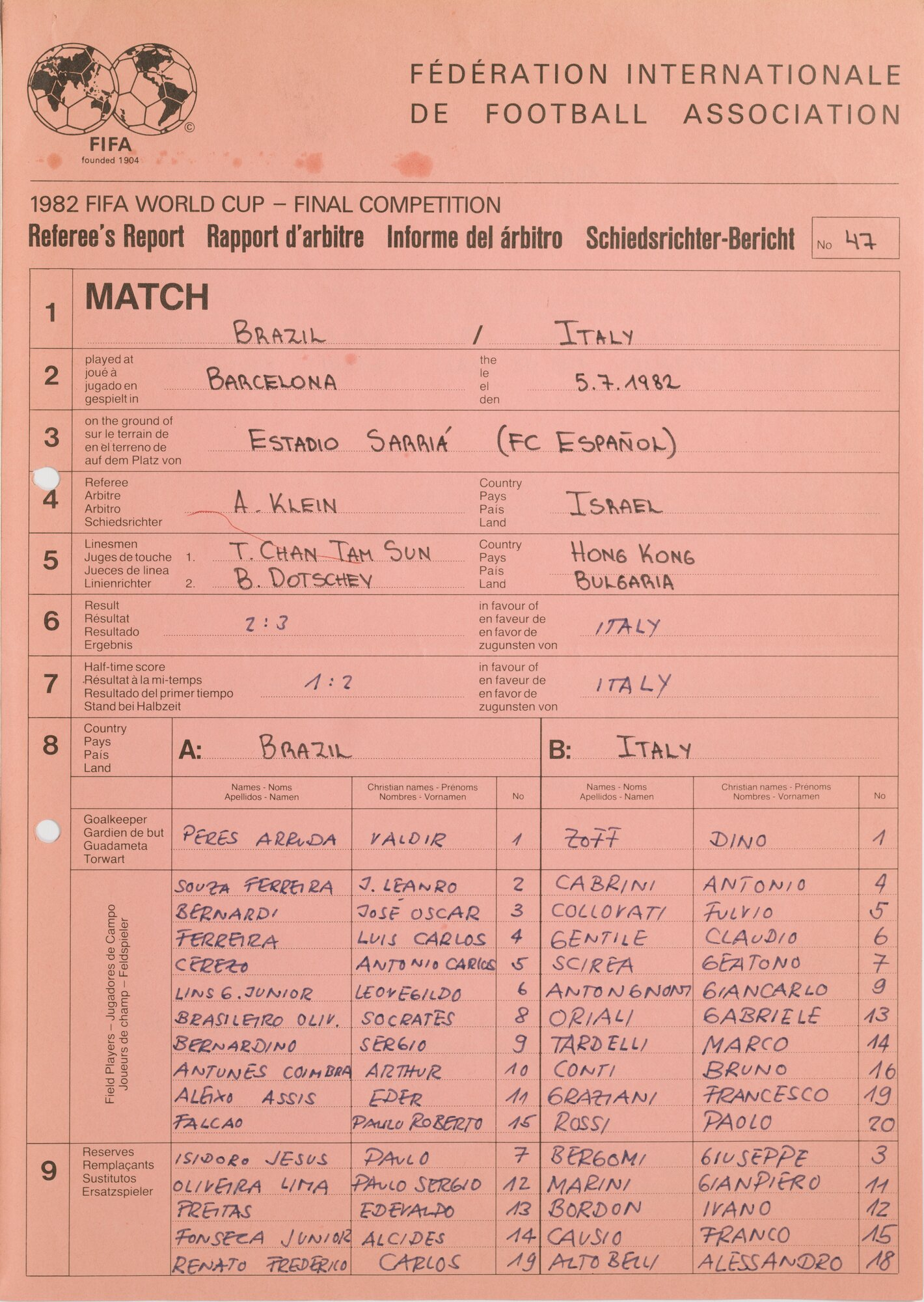

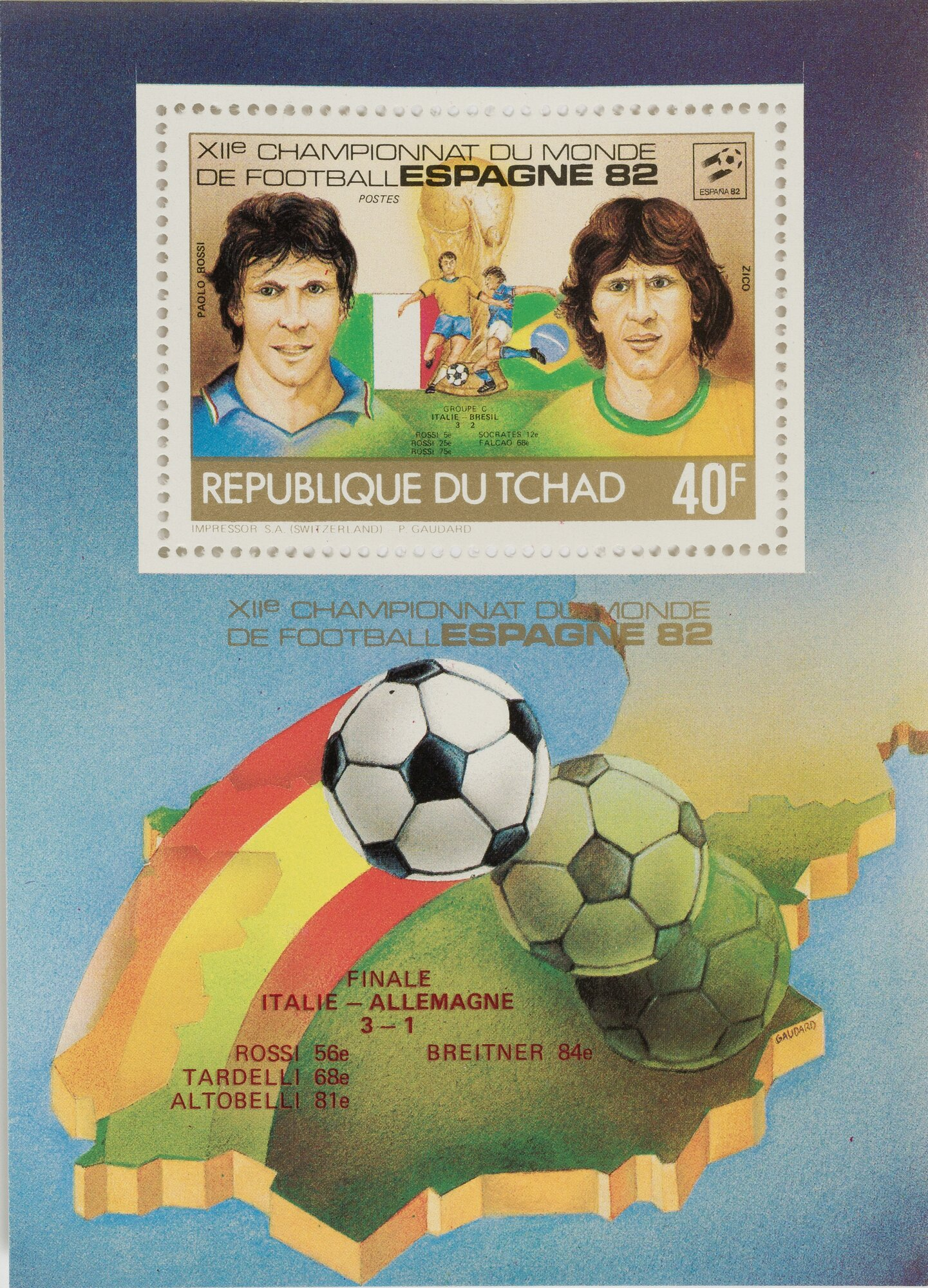

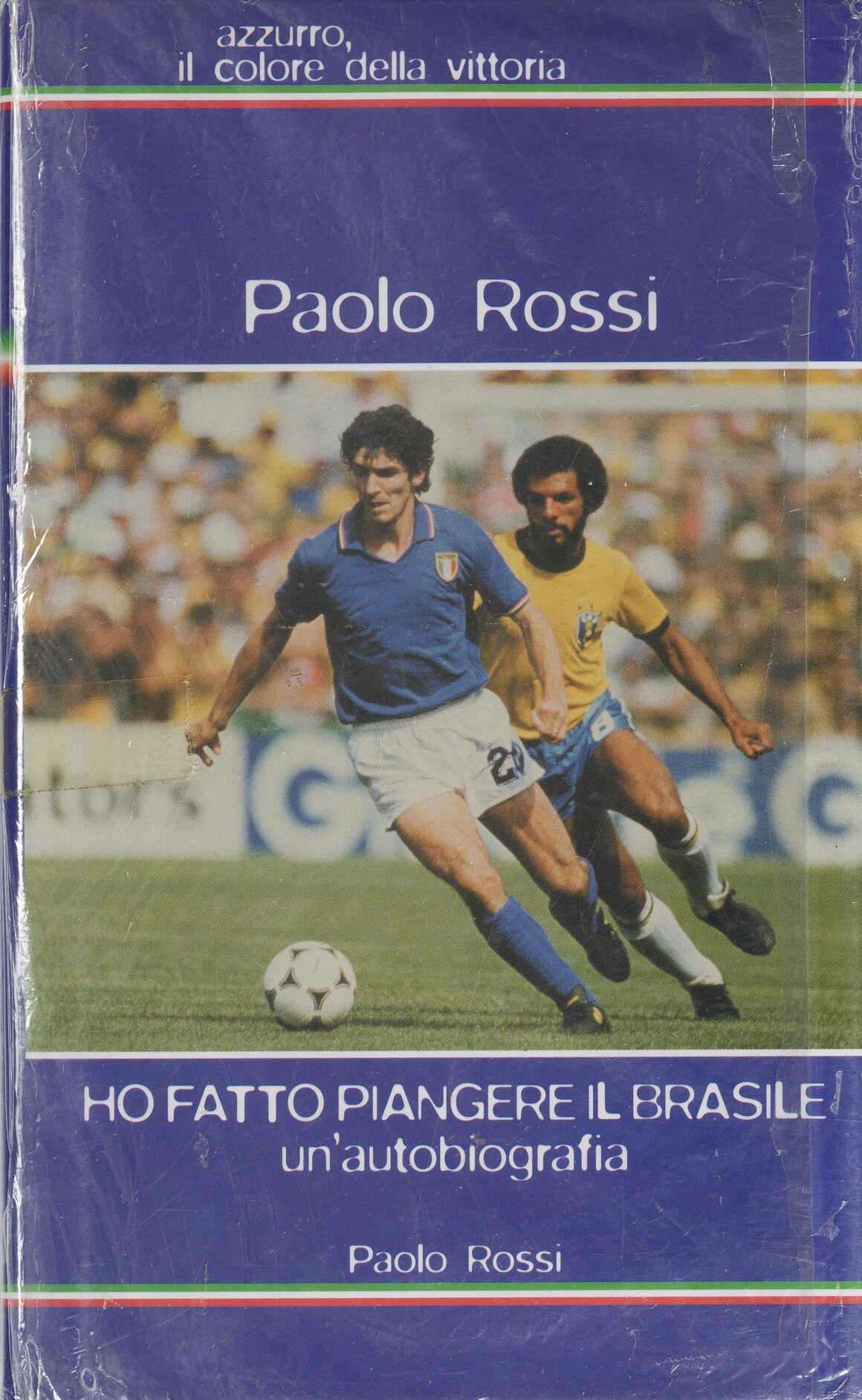

Paolorossi, I want to tell you that I was a midfielder, just like the founder of my football school, Arthur Antunes Coimbra—better known as Zico, O Galinho, the White Pelé, Brazil’s answer to Maradona. Dear Paolorossi, you have no idea how much I admired Zico, even though I never saw him play live. When he retired from Flamengo, I was seven years old. Then he went to Japan, and I attended the football school he founded. I watched so many of his tapes, so many videos: you know, Paolorossi, the way he took free kicks—no one else ever did it like that. The elegance he had with that number 10 on his back, for Flamengo, for the national team, and even in Italy with Udinese. I saw a great photo of you and him together in Italy on the internet: Zico in the Udinese shirt, you in the Juventus shirt. Ah, Italy. I’ve never been, but I’d like to go. It must be a beautiful place, even though for me “Italy” means “pain.” And that’s your fault, Paolorossi. I was born on July 5, 1982—the day of Brazil vs. Italy at the World Cup in Spain. You and Zico were both on the pitch in the match at Sarrià. Here, we don’t actually call it “the match at Sarrià,” we call it “the tragedy of Sarrià.” My father told me that all it would have taken was a free kick, that Gentile roughed up Zico the whole time. And doesn’t “gentile” mean “kind” in Italian? Instead, he mistreated him the whole match; just one whistle for a free kick at the right moment and O Galinho would have set everything straight.

Most of all, it would have been enough if you, number 20, and those tiny little boots, of yours, hadn’t been kissed by God that day. Paolorossi, I never met you, I never knew you, but I have to tell you that I was born on July 5, 1982, and everyone at my house was crying. I cried, like all newborns do, and my parents, my uncles, my whole family cried—and not out of happiness. In truth, all of Brazil was crying. Meu Deus, I was born on one of the saddest days in the history of my beloved homeland. Imagine being born on July 16, 1950—the day of the Maracanazo? Or a child born on July 8, 2014—the day of the Mineirazo? Every generation has its tragedy. But the day I was born, on the field was one of the most beloved Brazilian national teams ever: captain Sócrates, the heel that the ball asked God for, Toninho Cerezo, Falcão, Éder, Zico. What a team! My parents told me that everyone thought that World Cup was already won, and then you appeared on the field, Paolorossi.

If I had met you, I would have told you that it’s terrible to be born on the day your whole country suffers and never wants to remember again—truly terrible. It’s awful to be born on a cursed day. It’s awful to be born on the day you made my parents cry, you made Zico cry, you made Brazil cry.

But, Paolorossi, I envy you. As a footballer, I never experienced a day of grace like you did. I never had the chance to bring such immense joy to an entire country, but I was an athlete, so I completely understand what you felt that day and what you gave to all Italians. The best day of your life was the worst of mine—and it was my very first. In some way, you taught me that for every pain, somewhere in the world, there is a matching joy. Somewhere, someone dies and, at that very moment, a child is born. Somewhere, someone cries and, at that very moment, someone else shouts with happiness.

You gave so much of that, campeão, and you would have deserved even more.

I hate you and love you to death, Paolorossi.

Yours, Fabrício

“The heel that the ball asked God for”