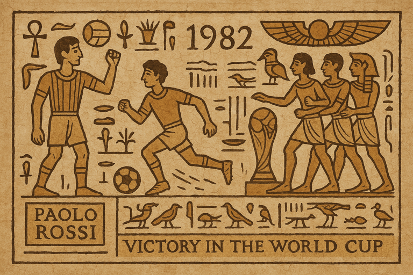

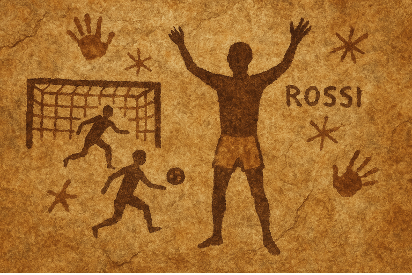

Humans have been telling stories since the dawn of time. Think of the oldest ones you can recall: before fairy tales, before the Odyssey, before Egyptian hieroglyphs and the Epic of Gilgamesh, there were cave paintings. Legendary hunts and epic escapes etched on stone walls, left for anyone passing by—even us, thousands of years later, can still immerse ourselves in those stories.

AI-generated image

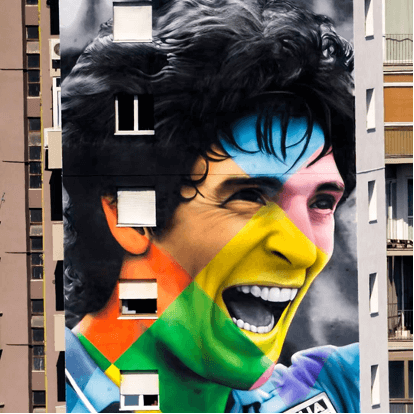

AI-generated image

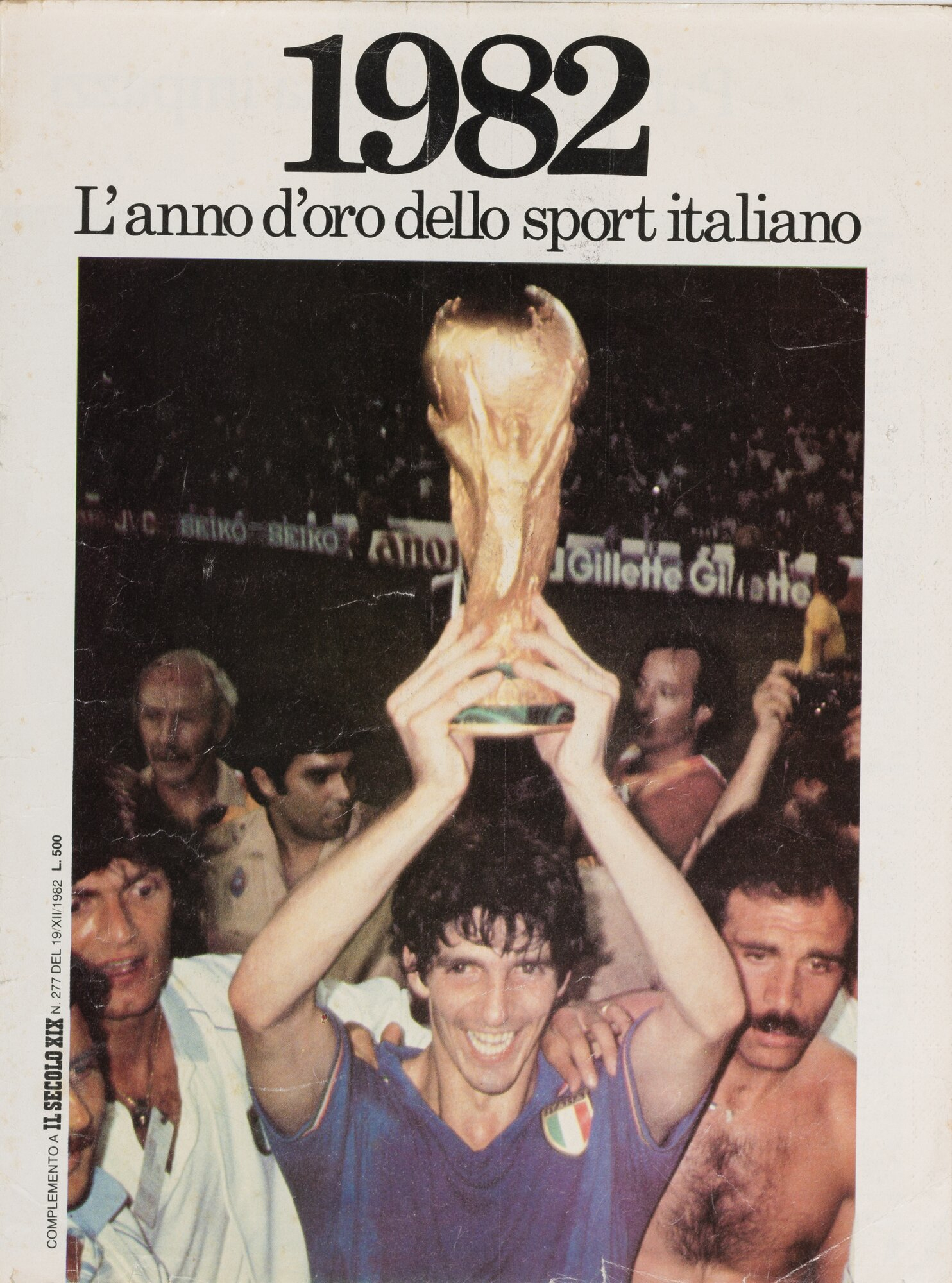

Today, those paintings have become graffiti, murals, and street art. Once clandestine and often a cry of protest, this art form has transformed the outskirts of cities into open-air museums. Over time, street art has earned the respect of the art world, paying tribute to figures and stories that everyone can agree on. Like Maradona in Naples, like Paolorossi in Vicenza.

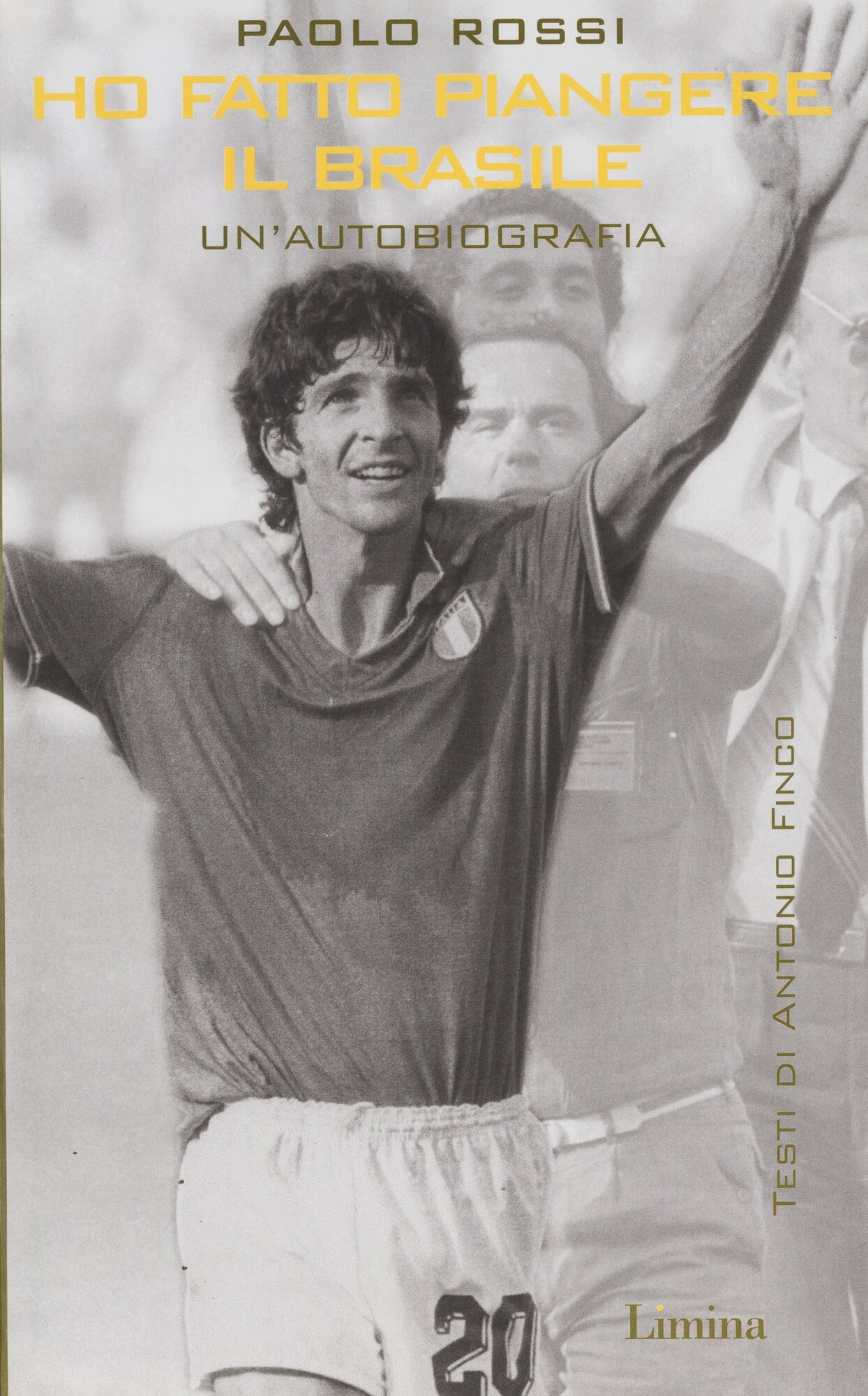

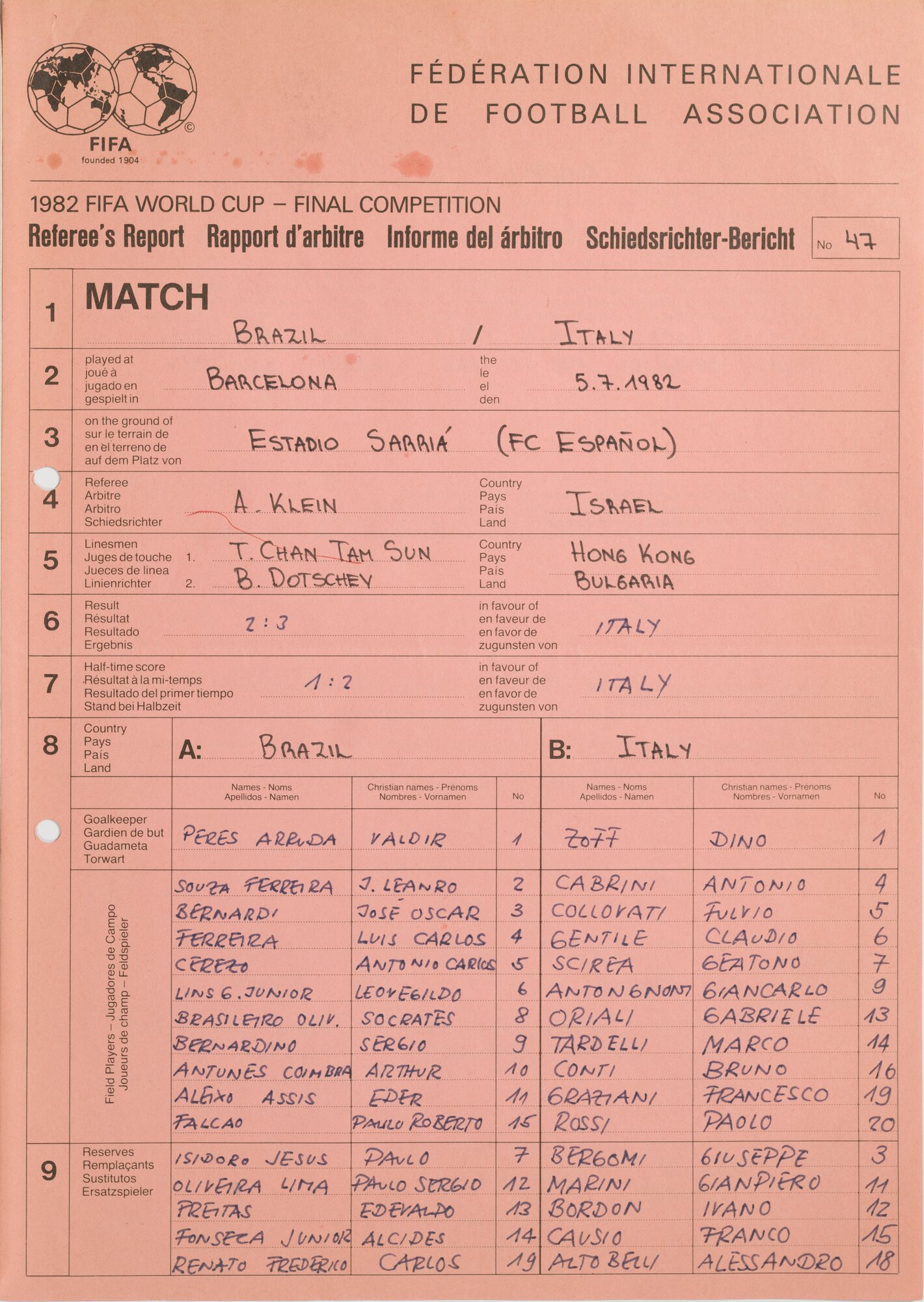

Paolorossi, the man who made Brazil weep with three goals in the legendary match of the 1982 World Cup, the man who, before becoming an international hero, was an icon for the city of Vicenza, where he left an indelible mark with Lanerossi. And it’s right here that the city decided to honor him with a monumental mural on the Everest Tower, 60 meters high, the tallest building available. The artist—perhaps in a twist of irony that Pablito himself would have appreciated—is Brazilian: street artist Eduardo Kobra.

"For us Brazilians, he went down in history as the executioner of our national team at the 1982 World Cup," Kobra wrote on his social media. "I was a child, and I remember it perfectly! But there’s no denying that Paolorossi was an extraordinary athlete and a man committed to causes I admire, like raising funds for children with heart disease. Creating this mural in Vicenza, the place of his first triumph, was an incredible challenge."

And so, in the heart of Vicenza, the image Paolorossi loved most, the one he wanted to be remembered by, now towers above the city. But the tributes to Pablito don’t stop there: along the city’s streets, his small silhouettes pop up everywhere, witnesses to a love that has never faded. To paraphrase a famous Brazilian song, Paolorossi is the color of this city, and his is the song of this city.

«Meanwhile, Melquíades finished capturing on his plates everything that could be captured in Macondo, and left the daguerreotype equipment to the delusions of José Arcadio Buendía, who had decided to use it to obtain scientific proof of the existence of God. Through a complicated process of overlapping exposures taken in different parts of the house, he was sure that sooner or later he would get a daguerreotype of God, if He existed, or else put an end once and for all to the hypothesis of His existence.»

Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

José Arcadio Buendía, in one of Gabo’s most beautiful passages, decided to scientifically prove the existence of God. The method he chose was daguerreotypy. If God existed, sooner or later he’d manage to capture His image; if not—if he couldn’t imprint even a shadow—then it would mean God didn’t exist.

The daguerreotype is a forerunner of photography, and in Louis Daguerre’s day, it was more than art: it was the meeting point of the artist’s gaze and the chemist’s knowledge.

In fact, the debut of daguerreotypy didn’t take place in a gallery, but at a joint event of the Academy of Fine Arts and the Academy of Sciences.

To make a daguerreotype, José Arcadio Buendía would have needed long exposure times: more than ten minutes to capture a single image. Ten minutes is an eternity, especially if you think about the fleetingness of a gesture—like a celebration-which would have needed far less time to be captured in a photograph. But how do you explain such a fleeting gesture? How do you capture it without freezing it? It wasn’t a matter of absence, but of patience, of time, of practice.

As the years passed, photography improved, and one day Eadweard Muybridge managed to freeze a horse’s gallop using 24 cameras, revealing something never seen before: the real position of a horse’s legs mid-gallop.

For some, it was a hard blow—many painters realized they’d almost always depicted horses incorrectly; some, it is said, even destroyed their canvases and changed professions. In short: Muybridge made painters cry.

A hundred years later, photographic technique had been refined to the point where athletic gestures could be captured with precision, but photography remained what it had always been: a reproduction of the visible. Period.

But one day, something invisible was captured in a photograph.

Alongside the smiling face, the shout of triumph, arms raised to the sky and clenched fists, woven together with the blue of the national team jersey, as intangible as the crowd yet present, were the years spent at the parish fields, the worn-out and broken boots, the road traveled and the one still ahead, hospital corridors and the desire to play (anywhere, as long as it was playing), two years of suspension and the return to the field, the fear of not making it, the determination to succeed, Bearzot’s trust, friendship, the joy of being there and everywhere at once, the awareness that from that moment on, there would always be a place in people’s hearts; even, in the end, in the hearts of those he had made weep, because just as Muybridge made painters cry, Paolorossi made Brazil cry.

If that photo had been taken by José Arcadio Buendía, perhaps…