CONSEQUENCES OF CONTAINING THE IMMEASURABLE WITHIN THE MEASURABLE: AN EXPERIMENT

Take a piece of the night sky and lay it down on the ground. To make observation easier, it’s best to cut it into a simple geometric shape—say, a quadrilateral, even better if it’s convex, perhaps a parallelogram.

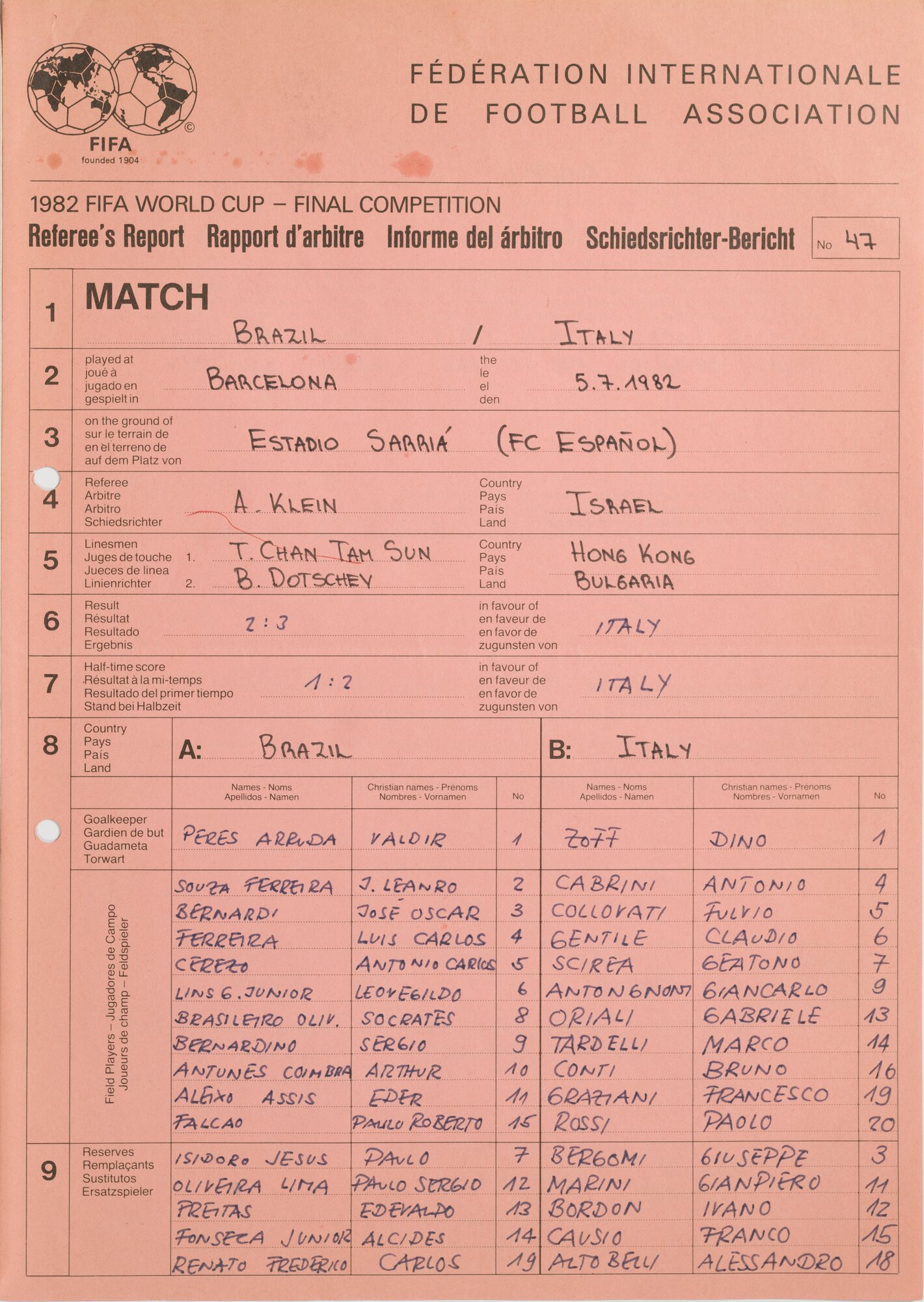

On a July night in 1982, near a beach in Barcelona, Aureliano borrowed his mother’s dressmaker’s scissors and climbed the rope ladder he used to reach the top of the chestnut tree in the garden, from where he could see everything. He only had to lean out a little to grab a corner of the sky, sink the tip of the scissors into the blue, and before you knew it, he started cutting.

Snip, snip, snip-he cut and cut, straight as the path of a gaze. The scissors glided smoothly through the celestial fabric, so much so that when he stopped, he realized he’d cut quite a bit—the first side measured 105 meters. Wow, thought Aureliano, I really got carried away. He laughed: time to turn the corner for the second side. He calculated ninety degrees and cut again, until he saw a rectangle of proportions he liked. He measured: 70 meters. Would you look at that, he thought, it’s as big as a soccer field.

He wrapped the rectangle of sky around his arm, tucked the scissors into his back pocket, and climbed down through the branches of the chestnut tree, then down the rope ladder and onto the ground.

He looked for a place big enough to lay out the sky and begin observing the immeasurable within the measurable.

He tried the Rambla: it fit lengthwise, but not in width.

He tried the Sagrada Familia and, in fact, it would have fit perfectly if not for the basilica’s forest of columns, the limits of the walls, the cross-shaped floor plan.

He wished he had his chestnut tree close at hand, so he could climb up and get a bird’s-eye view: where on earth could he lay out that piece of sky?

Then, with the eyes of someone determined to solve a problem, he saw it: the Sarrià stadium! He ran along Avenida Diagonal and didn’t stop until he was at the end line. With a decisive motion, he unrolled the sky—weightless—over the playing field. He climbed into the stands and began to observe.

Of the stars on the field, half gave off a cool, bluish light, while the other half glowed with a warm golden-green. Stars like these, in the July skies, we’ve all seen. Aureliano didn’t let himself be distracted by the beauty; he had his goal firmly in mind: to observe what consequences—if any—would arise from containing the immeasurable within the measurable. On that field of sky, those stars, feet firmly planted on the ground and driven by boundless desire, threw the system’s balance into crisis: it took only five minutes of observation for Aureliano to spot the star to keep an eye on. He had confirmation at the fifth, twenty-fifth, and then again at the seventy-fourth minute of observation.

He also noticed that the sky, however neatly cut by Aureliano, felt cramped at Sarrià; it pulsed and strained to return to being the sky. It held together on the ground for ninety-one minutes and then, elegant yet impetuous, went back to being the sky, leaving a trace behind. One of the stars got caught in the grass: tying his laces, wiping away sweat. Under Aureliano’s spellbound gaze, the star left on the field looked up and fixed his eyes on that sky he came from, with a longing so intense it made him shine. Aureliano recognized him: he was the consequence of containing the immeasurable within the measurable, and he called him Paolorossi.