“The textile companies of Prato in the 1860s distinguished themselves for producing red flannel for shirts and ‘blue cloth’ for the royal troops,” while in ordinary production they made “broad and narrow cloths, fine, semi-fine, and ordinary, plain twills and patterned fabrics, Cashmere, Vilton, Melton, Spagnolette, Flannels and Heavy Flannels, in white and colored.”

About a hundred years later, in Prato, Paolo Rossi was born.

Right there, in the city that once made the shirts worn by those who would unite Italy, and the uniforms of the army that would represent and defend it. Red and blue—colors that, in Paolo’s case, would shift towards the red and white of the many jerseys he wore throughout his career (Vicenza, Perugia), and the sky blue that, in 1982, would make Paolo the most famous man in the world.

He, too, was able to unite Italy, represent it, and defend it—he was made of the right stuff.

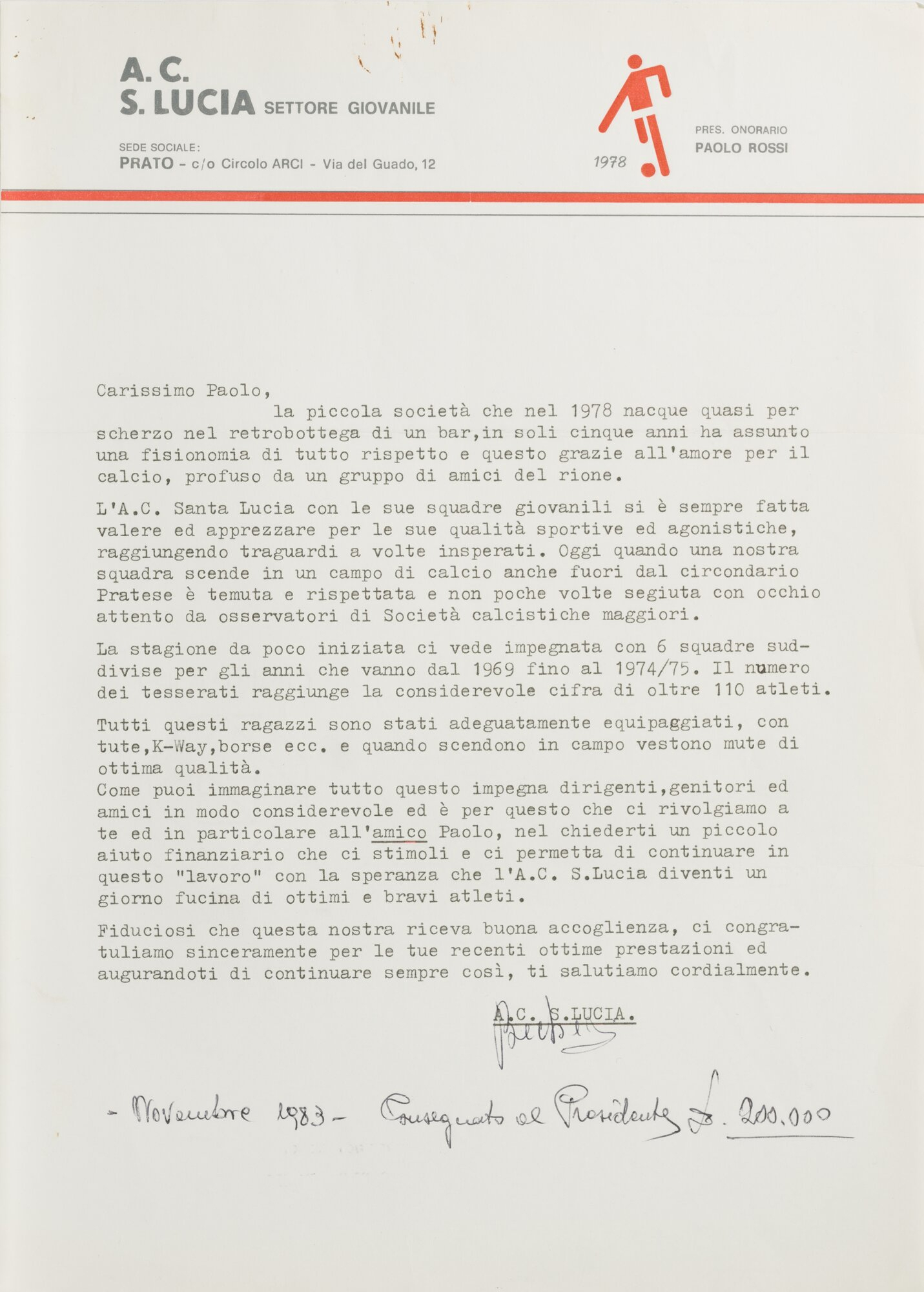

It all began in Santa Lucia, a district of Prato, where not only Paolo Rossi took his first footballing steps, but also Christian “Bobo” Vieri and Alessandro Diamanti. Like so many in those years, Paolo’s first kicks were at the parish youth center, but then Dr. Riccardo Pajar, the local physician, decided to form a youth team for the neighborhood: Sporting Santa Lucia. Just a few kilometers from Florence, football passion was nurtured through youth development, and Dr. Pajar, along with the managers of the small Santa Lucia team—which has since merged with neighboring Coiano—found the perfect formula to build one of Italy’s most prolific youth academies, launching champions towards Serie A and the National Team. It’s incredible that from that tiny corner of Tuscany came, to this day, the two best World Cup strikers of all time: Pablito Rossi and Bobo Vieri, who share this extraordinary record with Roberto Baggio. The pitch of the Santa Lucia team stood just a few hundred meters from the home of Amelia Ivana Carradori and Vittorio Rossi, Paolo’s parents, and his older brother Rossano—just a year older—who would also become a footballer. The Rossi family lived on Via Fucini, a place that became the destination for hundreds of people on July 11, 1982, right after the World Cup final in which Bearzot’s Italy beat Germany 3–1. For many, it felt natural to celebrate the victory beneath those windows, where the hero of Spain had grown up, just steps from the Santa Lucia field where Pablito had started kicking a ball at age nine, alongside his brother Rossano. Their father Vittorio had played as a right winger for Prato. In short, the Rossi family had football and textiles in their blood: mother Amelia was a seamstress; the grandfather, true patriarch of the family and so passionate about sports that he passed it on to his children and grandchildren, was a founding partner of Socit, a renowned Prato textile company; and father Vittorio, though he played football, had a “real” job as an accountant in a textile company’s administration.

Paolo Rossi’s football story—he admired Dr. Pajar so much that he would accompany him on his rounds to visit patients, even imagining for a while that he might become a doctor—began with the Under-13 Arcobaleno Cup, where Paolino scored 6 of the 10 goals that led Pajar’s Sporting to victory over Folgore. The die was cast: despite his mother Amelia’s doubts, there would be no stethoscope—football boots were the better choice.

In 2014, Angelo Carotenuto interviewed Paolo Rossi for Repubblica; there was a question about his strongest memory linked to the World Cup. A reply about his exploits in Spain seemed obvious, even taken for granted. But no, Paolo was once again able to illuminate an apparently minor detail, but not for him:

“It was 1978, the day Bearzot told me I would play against France. We were traveling from Buenos Aires to Mar del Plata, standing at the foot of the airplane steps, when he came over and said “Get ready.”. I thought of the joy my father, far away, would feel. That’s the moment in my career I remember most often.”

Paolo Rossi was honorary president of Coiano-Santa Lucia, which now plays its matches at the “Vittorio Rossi” sports field, named in memory of Pablito’s father.