FAIRY TALES ARE TRUE

“I believe this: fairy tales are true”, wrote Italo Calvino.

So the enchanted forest and the magical castle are real, the dark lairs and the dragons who inhabit them are real, the curses are real and so are the prophecies.

If the fairy tale is true, reality slips into fantasy and begins to inhabit it with the tools of everyday life: beans, spinning wheels, broomsticks, cauldrons, grinders, even shoes of every shape and size.

The boots the cat asks of the miller’s son, or those that Tom Thumb steals from the ogre, the red shoes that never stop dancing, or the silver ones that allow Dorothy to return home to Kansas, the glass slippers that will show the prince, the stepsisters, and the whole world the uniqueness of Cinderella.

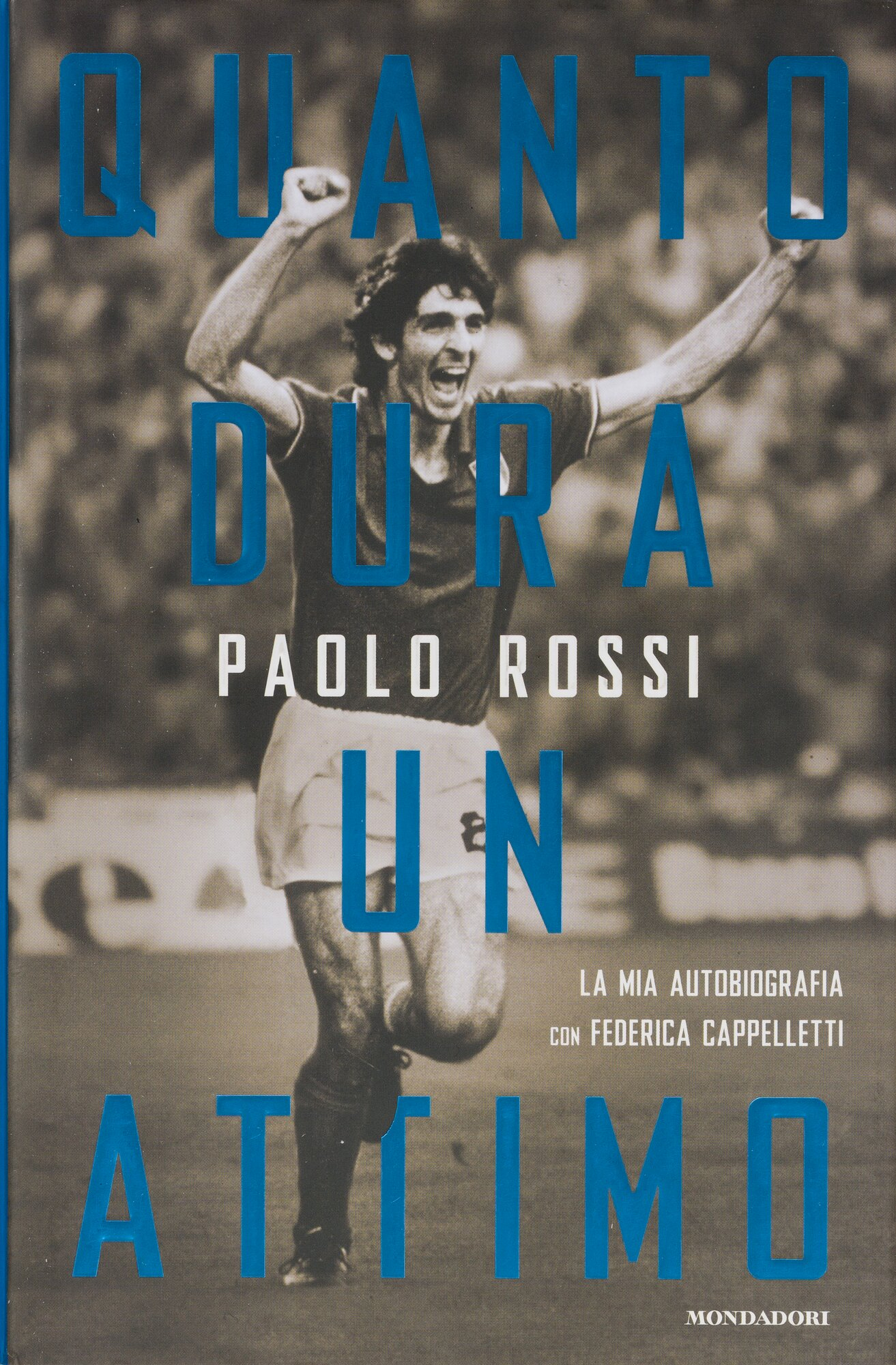

And the cleats of Paolorossi, are real too—those very shoes that, in 1982, accompanied not only Pablito step by step on his adventure, but made the whole world fall in love with Italian football through the fairy tale of a village boy who, from a countryside parish, breathing in the sharp air of a land where olives grow and listening to the rhythmic sound of a sewing machine, climbed all the way to the top of the world, stitching onto himself the uniform of a champion, to reap the sweet fruits of someone who managed to cultivate his own dreams.

We know well that it’s the wand that chooses the wizard, and even if those cleats would have served other football artists, just as well, it was their union with Pablito that took everything to another level. The 1982 World Cup didn’t get off to the best start for him.

He would later recall that his self-esteem was low, but the boundless trust Bearzot placed in him was crucial.

“I don’t know what other coach would have kept starting me, while an entire nation was relentlessly hammering him to change his mind […] The first goal against Brazil was the most important of my career, because it restored my confidence in every way. A goal, when it comes, is like manna from heaven for a striker […] From that moment on, it felt as if someone up above was looking after me. Nothing was going my way and, all of a sudden, the wind changed. A goal can be revolutionary and, for me, it literally changed my life.".

On the night of those three revolutionary goals that, for him, literally changed his life, Pablito was wearing those very cleats. Exactly those.

Out to get someone

This expression, “fare le scarpe a qualcuno” (“to make someone’s shoes”),, has entered everyday language with a negative connotation. We know it: to “fare le scarpe” means to trick someone, perhaps to oust them from their position.

The expression may have originated in the military or, alternatively, among the lords and notables of the seventeenth century. In the first case (though there’s no proof, just a lot of clues), we’ve seen plenty of films, especially war movies, where the survivors steal the shoes (or boots) from fallen soldiers; Rossellini’s Paisà offers a less gruesome example: little Pasquale, a Neapolitan orphan, steals the shoes of Joe, an American soldier, taking advantage not of his death but of his drunkenness. As for the second case, it seems that among people of a certain rank there was a custom of being buried in new shoes; in that context, “making someone’s shoes” could be a portent, a wish, or a threat. In any case, there wasn’t much to be cheerful about.

Fortunately, people like Ettore Petrolini have spoken well of new shoes. In what is probably his most famous song, he tells us that “All you need is good health and a pair of new shoes, and you can travel the whole world.” So, these new shoes that can take you around the world—someone has to make them, literally.

Let’s take a look at a part of the process needed to make someone’s shoes: the last factory.

There’s a renowned one in the heart of Italy, in Forlì; it’s called Formeria Romagnola, and as it happens, it belongs to a family named Rossi—no relation to Pablito and his, but as we know, “Rossi” is the most common surname in Italy.

The “formeria,” as the name suggests, makes the lasts for shoes.

et’s imagine the traditional technique. In the past, lasts were made of metal and only from the sixteenth century did they start making them from wood (and it wasn’t until the nineteenth century that they differentiated between left and right). Before the advent of (recycled) plastic, you’d start with a block of wood, a nice parallelepiped from which, with skill and patience, you’d remove the excess until you reached a shape that was both comfortable to wear and aesthetically pleasing. When it comes to shoes, we all know that even a single millimeter can make the difference between sore feet and comfort, between a limp and a smooth stride. In Paolorossi’s case, the difference between a goal (and then another, and another) and a missed chance. So, on with the rasps of different grains, sandpaper, and expert hands, until from that block of wood—which had the potential to become anything, from a puppet to a shoe model—the perfect last emerges.

Once the last is ready, smooth and polished, it’s marked with an identifying (and sequential) number. In the historical archive of Formeria Romagnola, not only is number 1 preserved, but lasts of all types and models—even clown shoes and ballet pointe shoes. Prada shoes, Harley Davidson, Louis Vuitton, Rita Ora… and then the shoes of: Kevin De Bruyne, Samuel Jackson, Kevin Durant, Michel Platini, Pope John Paul II.

And of course, with serial number 22712, there’s also the last for Paolorossi’s shoes.

Who knows—maybe a bit of the emotion Pablito gave us also passed through the hands of those who made his shoes.