To talk about the bond between Paolo Rossi and Turin, let’s start here: it’s July 11th, 1982, when the Rolling Stones play their first concert in Italy since 1970. They do so at the Stadio Comunale in Turin, where Pablito had played and scored for Juventus.

Mick Jagger wears the number 20 jersey of the Italian national team, gets hoisted up by a crane draped in the tricolor, and rises twenty meters above the field. He predicts that Italy will defeat Germany 3–1 in the World Cup final in Spain. And that is exactly what happens.

Paolo Rossi’s story is one of magical realism, of intuition, of premonition. This one is especially fascinating because it unfolds from a modern pulpit, spoken by a god of music, in the cathedral of the stadium that, just three months earlier, had seen Paolo return to football after the injustices he suffered. Paolo managed to play three matches in the 1981/82 season after his suspension ended: he returned in Udine, on May 2nd, 1982, even scoring a goal. Then he reappeared before the Juventus fans on May 9th, 1982, against Napoli—a match that ended 0–0.

At the start of the match, some fans paraded along the athletics track at the Comunale, carrying a banner: “Welcome back, Rossi.” It was the penultimate match of the season, and that half misstep allowed Fiorentina to catch up with Juve: on the last day, Catanzaro–Juventus ended 0–1 with a penalty by Brady fifteen minutes from the end, while Fiorentina failed to beat Cagliari away. Juventus won their 20th Scudetto, the one with the second star. After that single appearance on the Comunale pitch in Turin, before Mick Jagger, Paolo—much to everyone’s surprise—was called up to the national team by Enzo Bearzot, but things didn’t start well:

“I was a ghost, but the trust of my teammates and the coach gave me incredible strength. The guys joked that I could barely stand on my feet. From stress, I’d lost five kilos. And I remember the cook brought me a glass of milk and a brioche to my room every night. After every match, Bearzot would say to me: 'Don’t worry, now get ready for the next one.'”

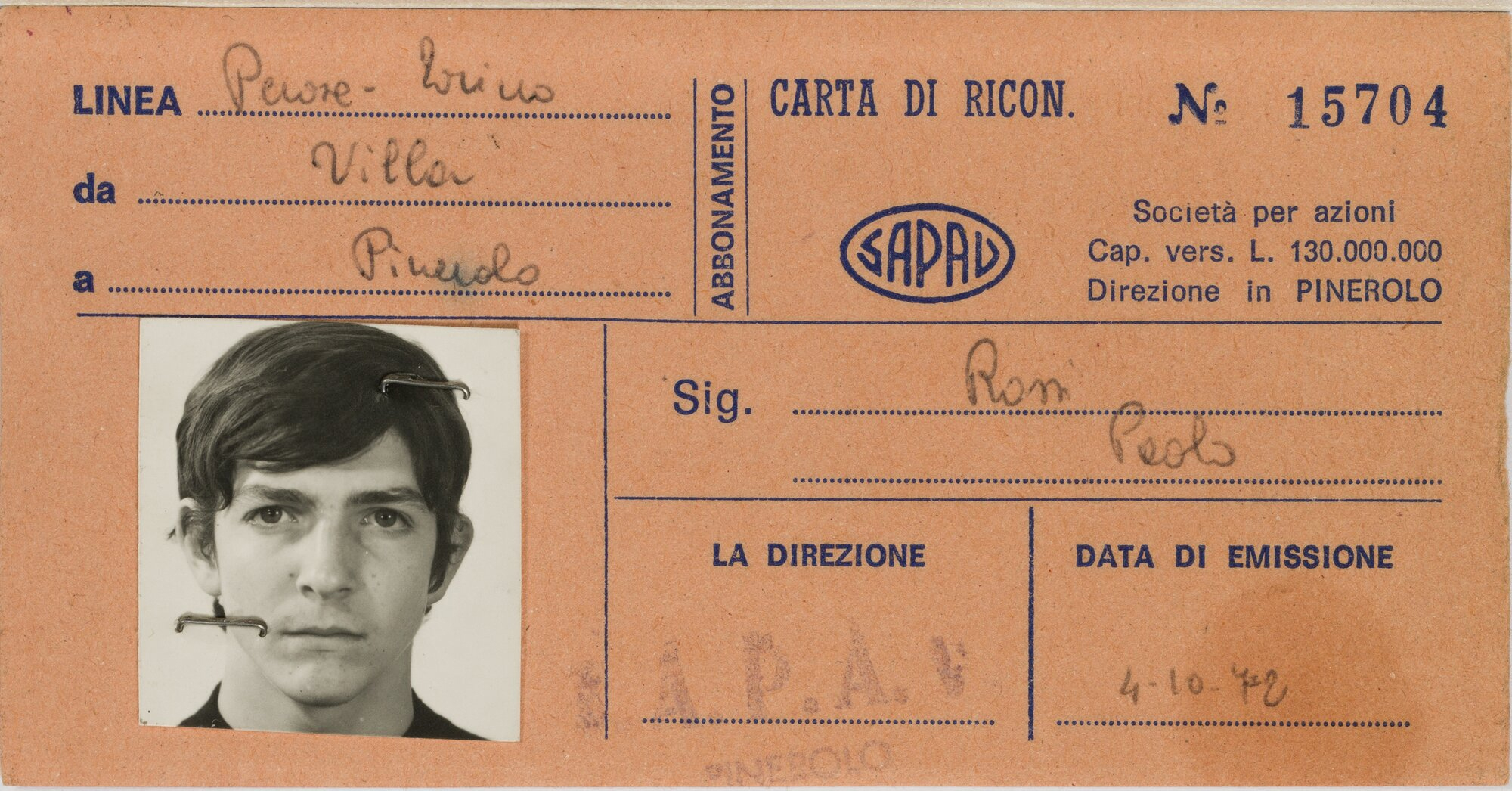

We all know how it ended, but Paolo Rossi’s story in Turin begins in 1972. He was sixteen years old.

“It wasn’t easy—my parents were against it. They’d been burned by my brother Rossano’s experience: he was also with Juventus, but sent home after just a year. My father advised Cattolica Virtus of Prato to ask for a high fee to discourage the Juventus directors, but it was no use: for fourteen and a half million, I packed my bags.”

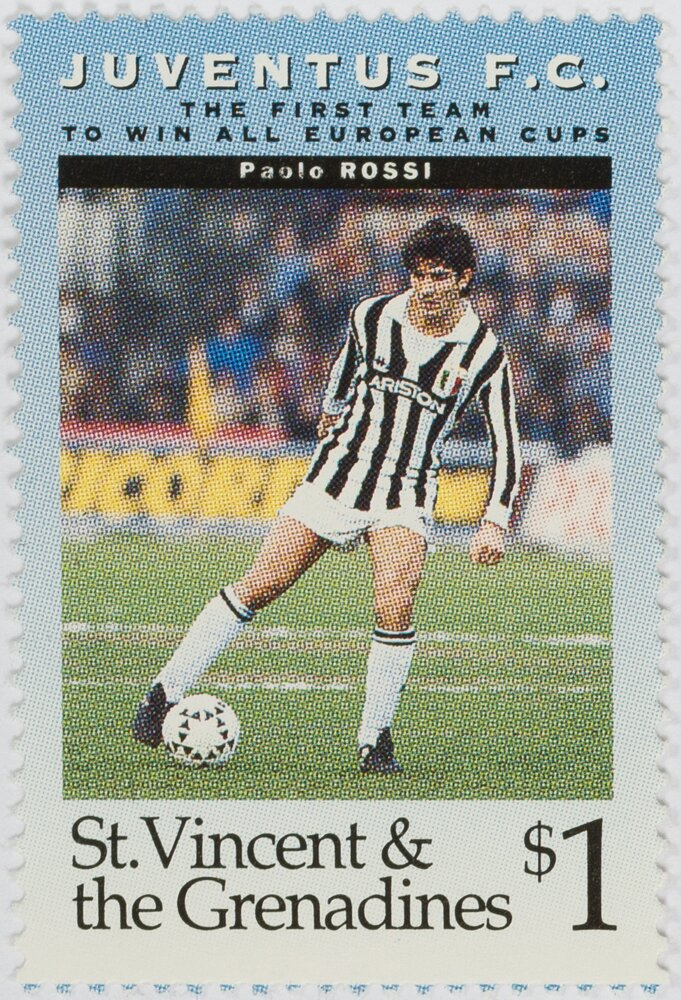

In Turin, however, his journey through the youth ranks was interrupted by a staggering series of injuries. On May 1st, 1974, not yet eighteen, he finally made his first-team debut against Cesena in the Coppa Italia: he played for the first time with Dino Zoff, Claudio Gentile, and Franco Causio, with whom he would later become world champion.

The fragile boy who, in the early ’70s,

took the coach to Villar Perosa for training, dafter paying his dues at Como, exploding at Lanerossi Vicenza, and the experience in Perugia, would return to Juventus a man, marked by the injustice he had endured. After two hellish years, another call would come from Turin—on the other end was President Boniperti:

“You’ll come with us to training camp, you’ll train with the others—in fact, more than the others.”.

Paolo felt like a footballer again; that call-up letter telling him to turn up with short hair and what to eat and drink made him feel reborn.

With the Bianconeri, he would play 83 matches, score 24 goals, win two Scudetti, a Coppa Italia, a Cup Winners’ Cup, a UEFA Super Cup, and a European Cup-the ill-fated one at Heysel. With him, Juventus would become the first team to win every European trophy, and above all, in the black-and-white jersey, he would meet two lifelong, brotherly friends: Paolo Cabrini and Marco Tardelli.