A Metropolitan Biography

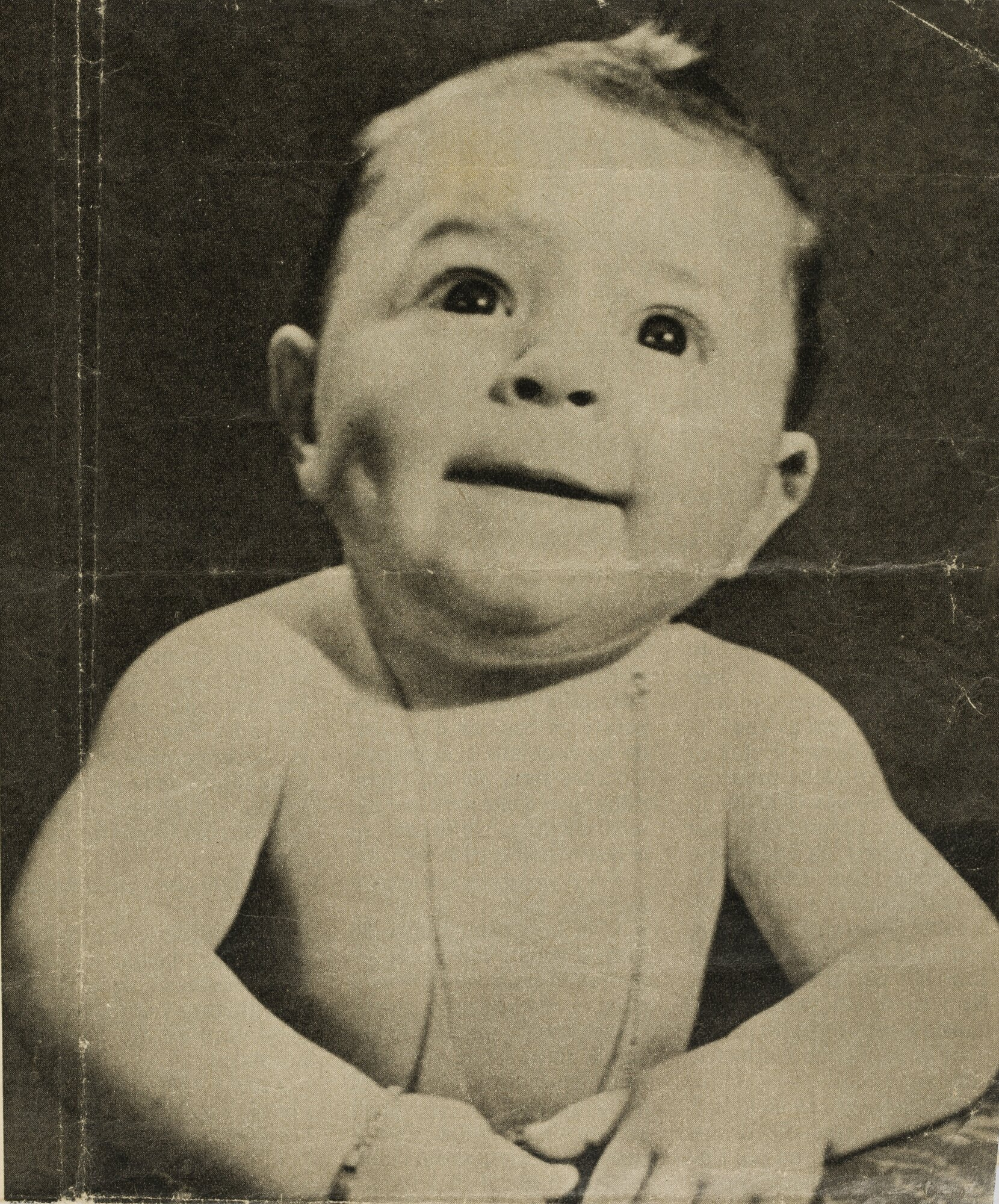

According to Wikipedia, the most common surname in Italy is Rossi, found in no fewer than 4,572 towns, with a total of 60,487 families. One of these families had the fortune of giving a little brother to their firstborn, Rossano. It was Sunday, September 23, 1957, the hour of the football championship, when, in Prato, Paolo Rossi entered this world—and, in a way, never left it.

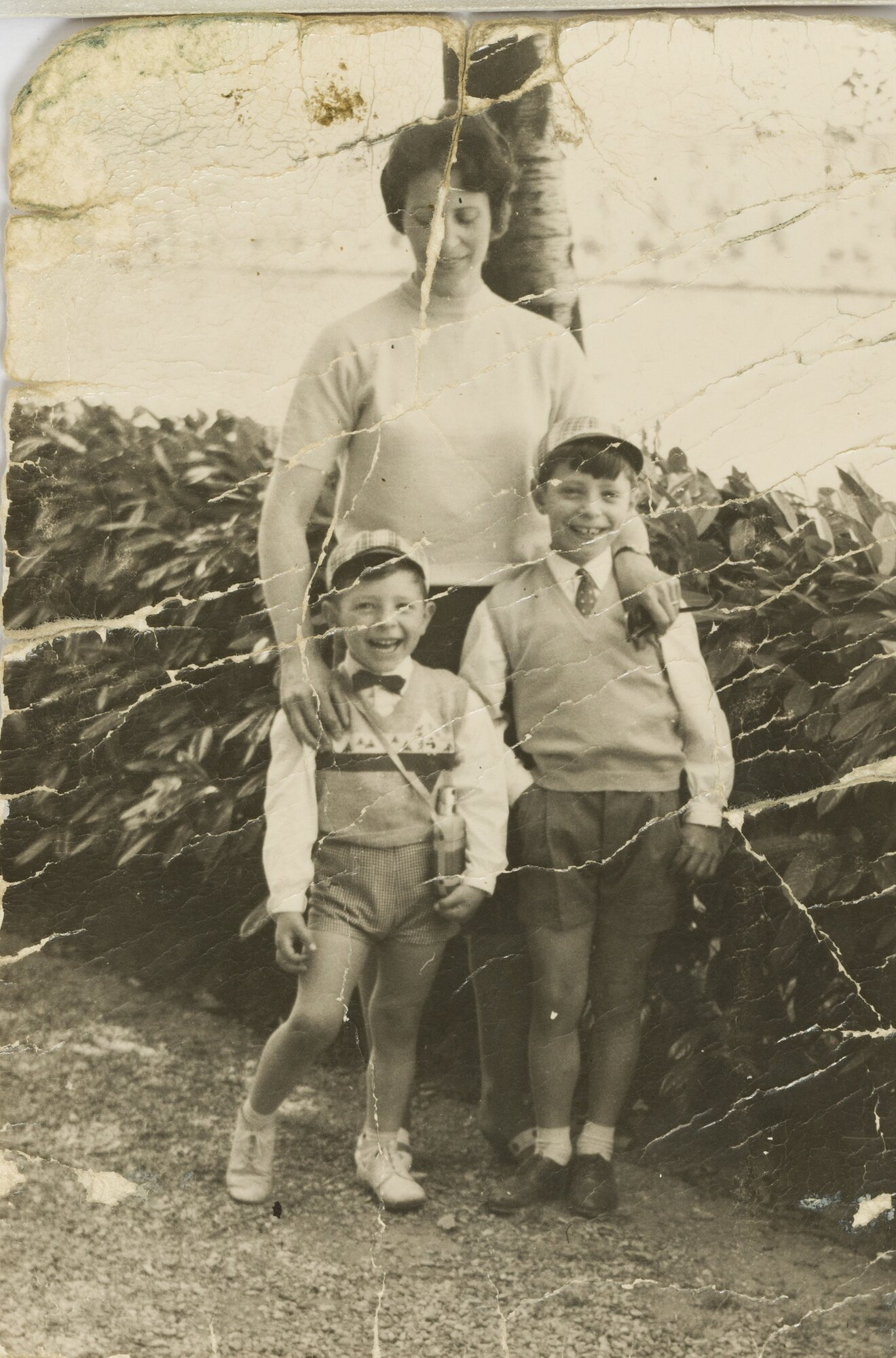

Paolo—or rather, Paolino—is a lively child who falls in love with a football from the very start, just like, his brother Rossano. They play at the Santa Lucia parish, a district of Prato, and Paolino goes through an incredible number of football boots, something that weighs heavily on the family’s finances. The Rossi family is not well-off: their father, Vittorio, works as an accountant in a textile company, and their mother, Amelia, is a seamstress. That both sons are passionate about sports is normal—sporting competitions, and especially the national team, are a family passion. It’s no wonder, then, that the tricolor jersey is the one Paolino dreams of wearing someday. He does well at school, he’s curious, but when he thinks about the future, he imagines something different from what his mother would choose for him: she hopes for a stable, secure job, maybe as an accountant; he, on the other hand, sees himself on the grass of a football pitch.

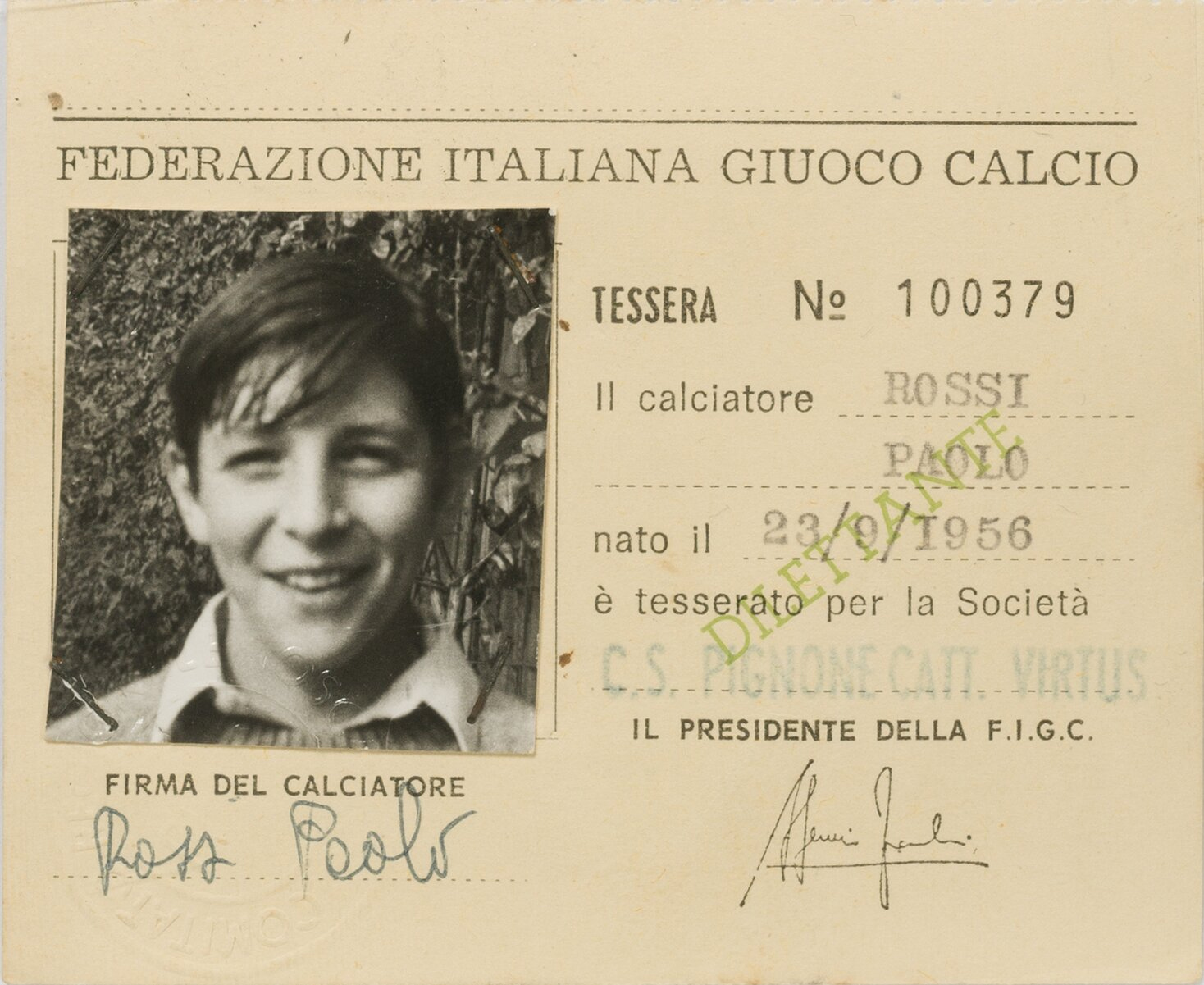

Paolino’s dream makes sense, because when he plays football, he has something extra—sometimes it’s as if he’s living a moment ahead of everyone else, so naturally does he find himself in the right place at the right time. His talent doesn’t go unnoticed, and while a sports career isn’t yet a certainty, he receives his first player card with Cattolica Virtus, in Florence. Soon enough, people a bit further north—in Turin—take notice: Juventus wants him for a stint with their youth team. Paolino would leave in a heartbeat, but things aren’t so simple; after all, you have to convince the parents of a boy who’s only fourteen to let him go—and to accept what that life would mean.

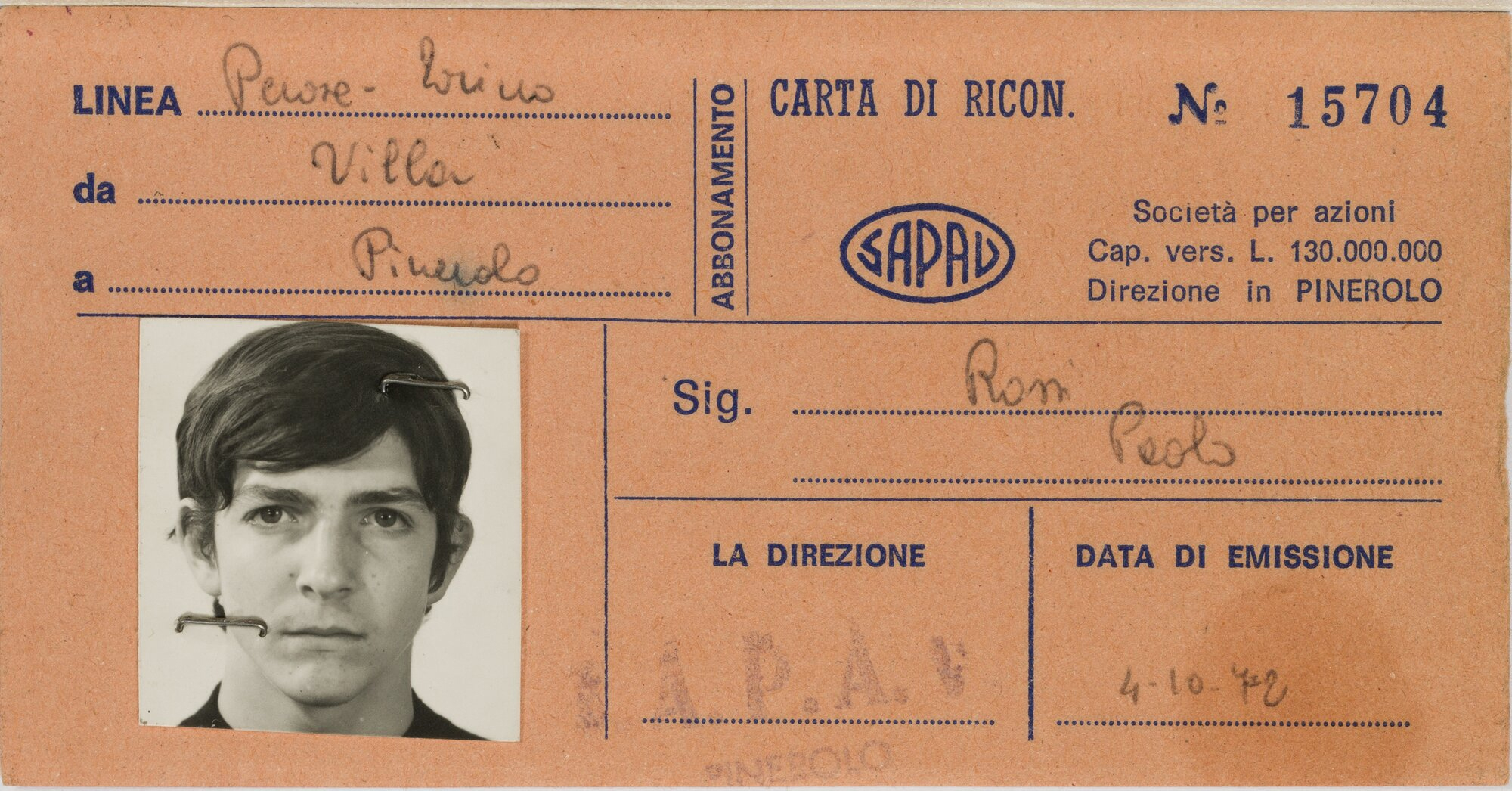

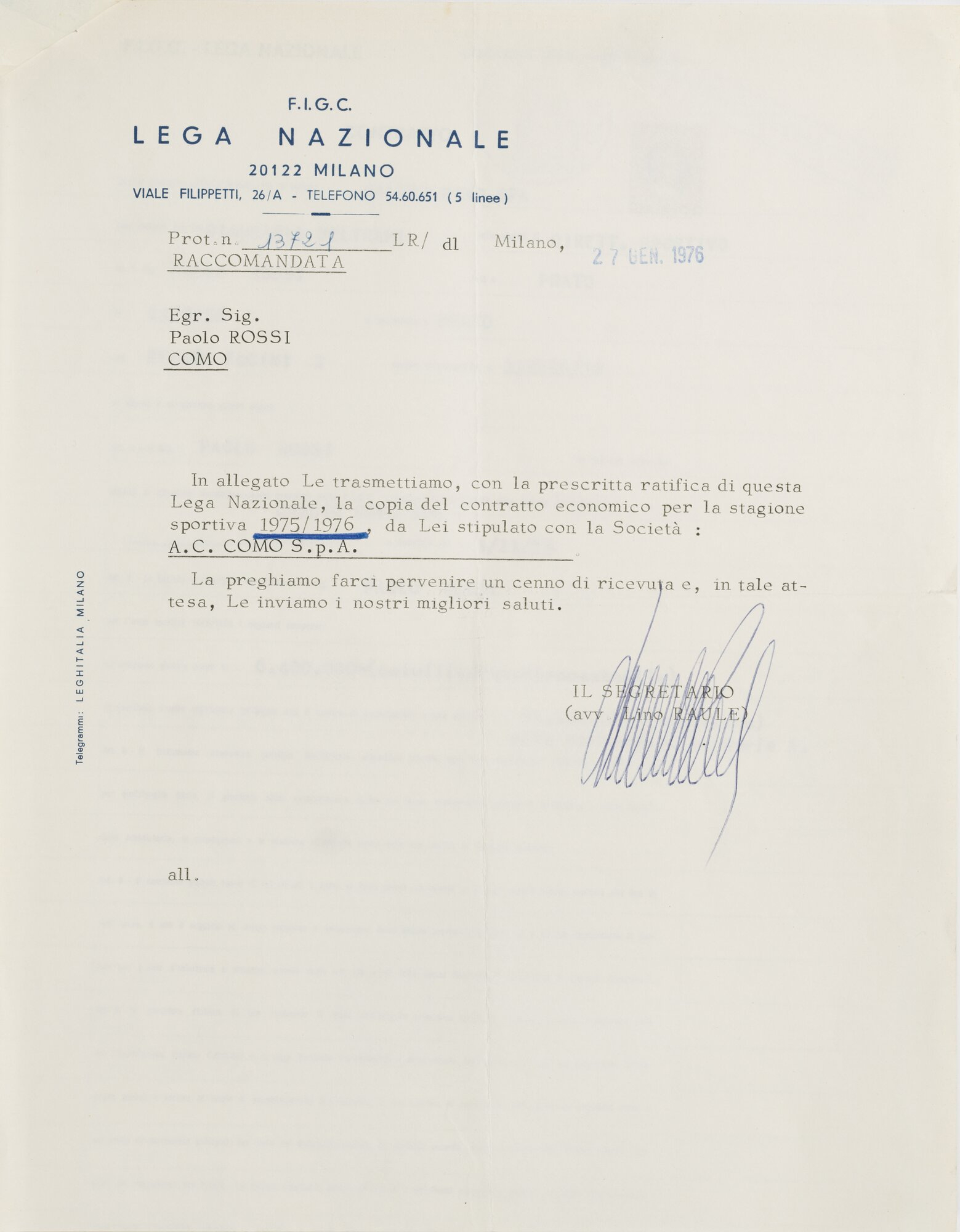

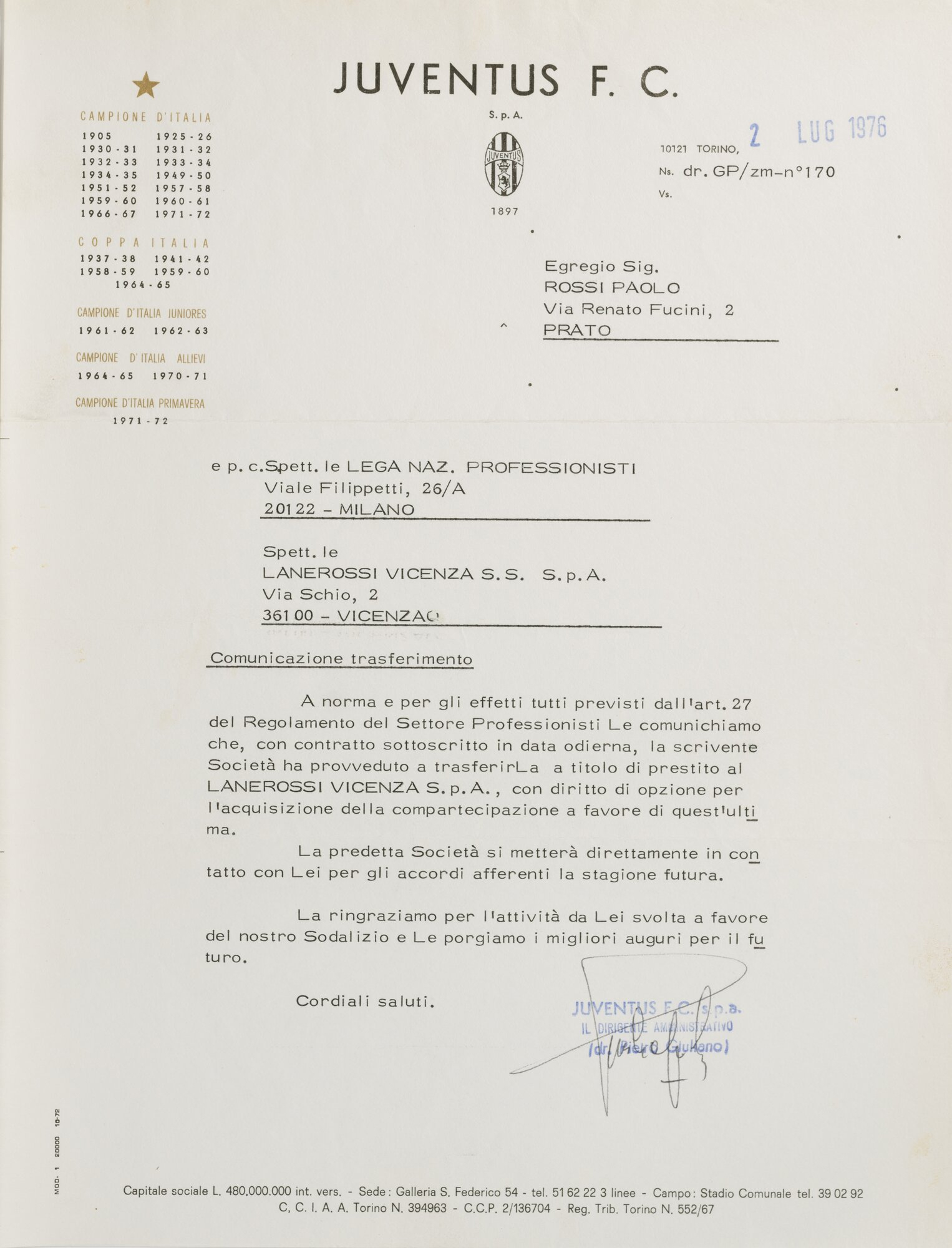

Nonetheless, the deal goes through, and soon Paolino finds himself lshuttling between Pinerolo, where he goes to school, and Villar Perosa, where he trains. The team is thrilled with Paolo—a little guy who slips away like a bar of soap—but stories need complications to become memorable, and in the span of two seasons, he tears three menisci. The physical pain, the fear he’ll never return to the level required for a serious team, the impatience, the shoes that, even if not yet hung up for good, still gather dust. But Paolino comes back. His contract belongs to Juventus, but they send him to Como to toughen up; except at Como, Paolino spends more time on the bench than on the field, and finally, in desperation, he asks to be sent anywhere—anywhere, as long as he can play. And anywhere it is: he ends up in Serie B, on loan to Lanerossi Vicenza.

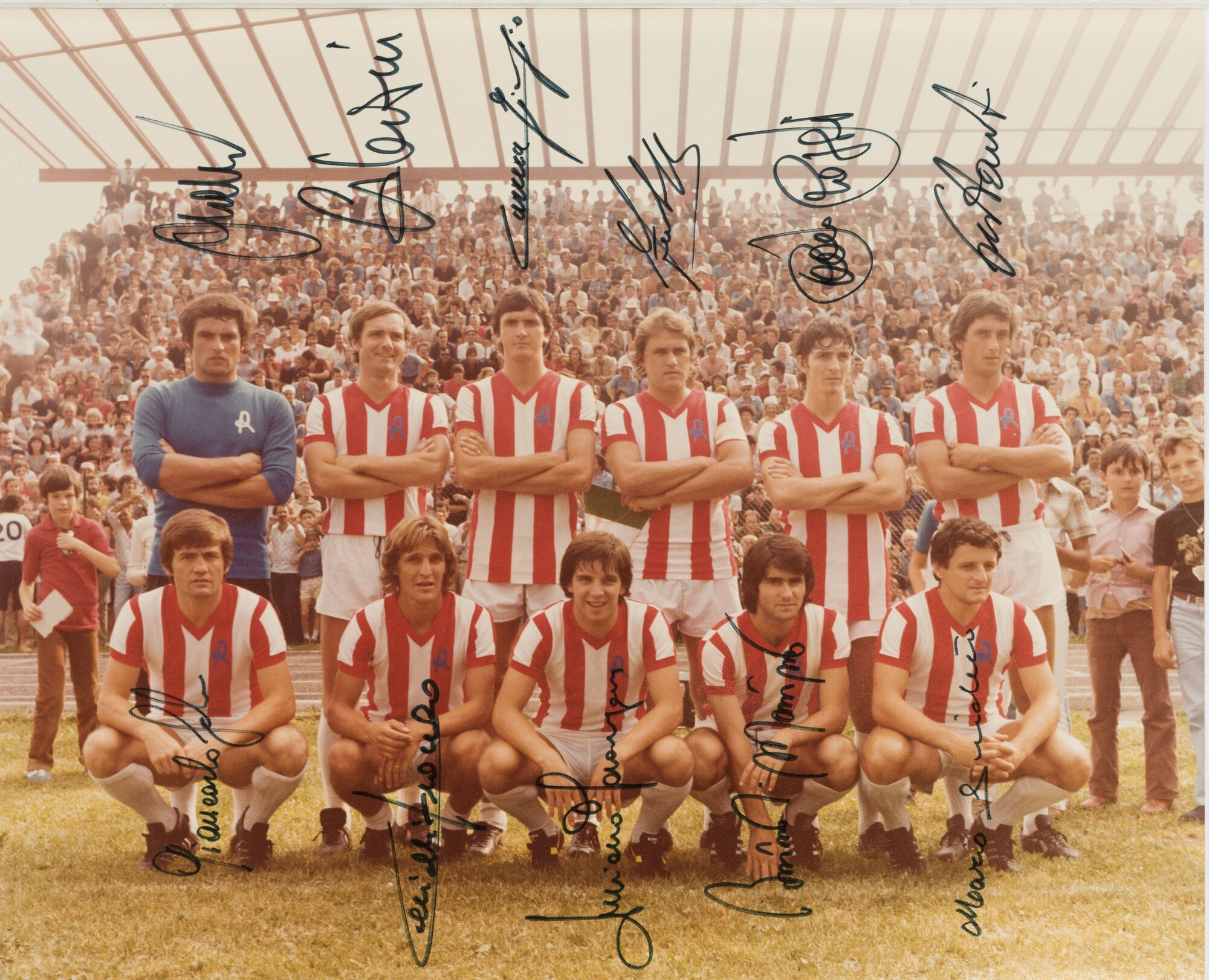

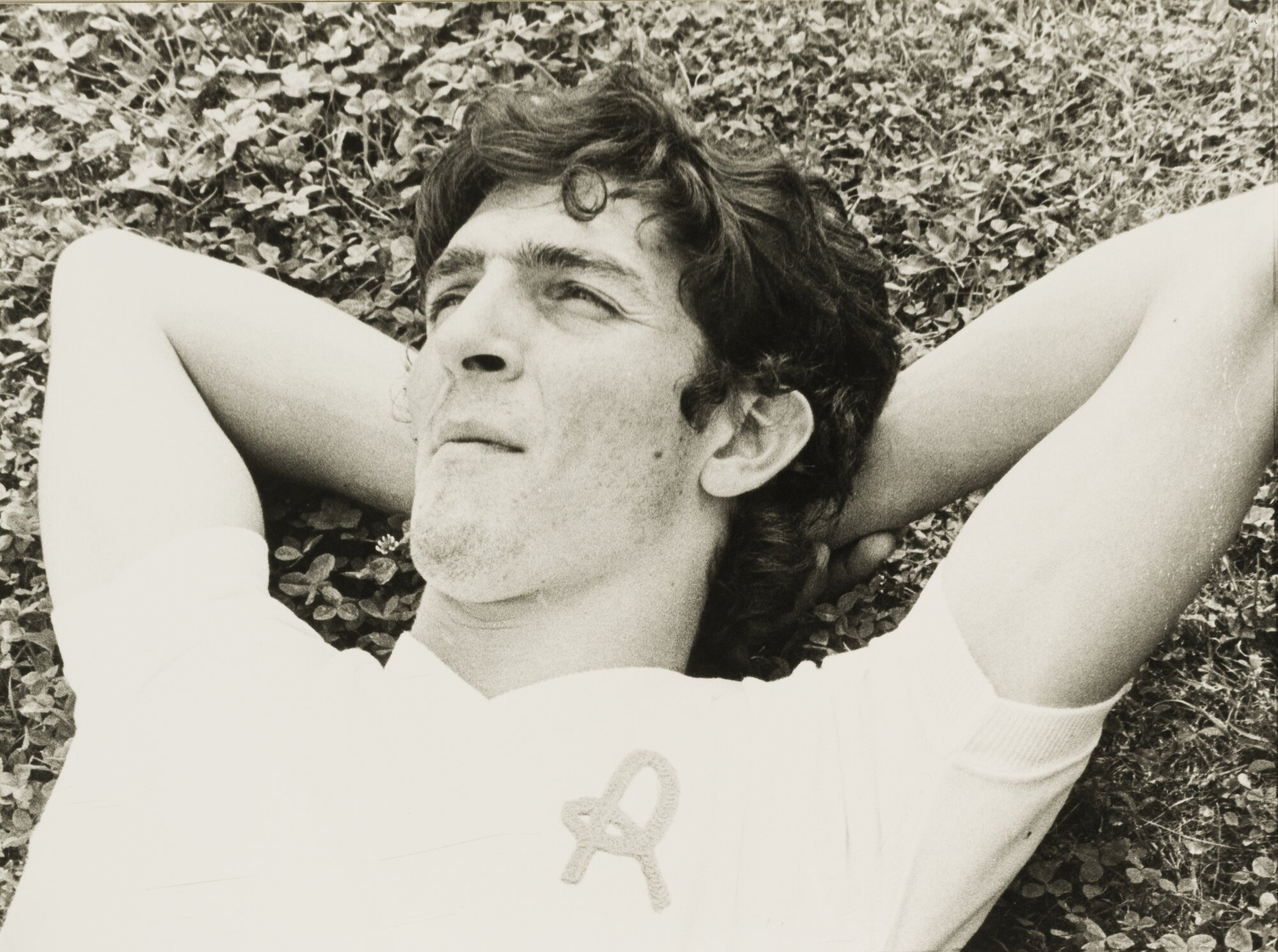

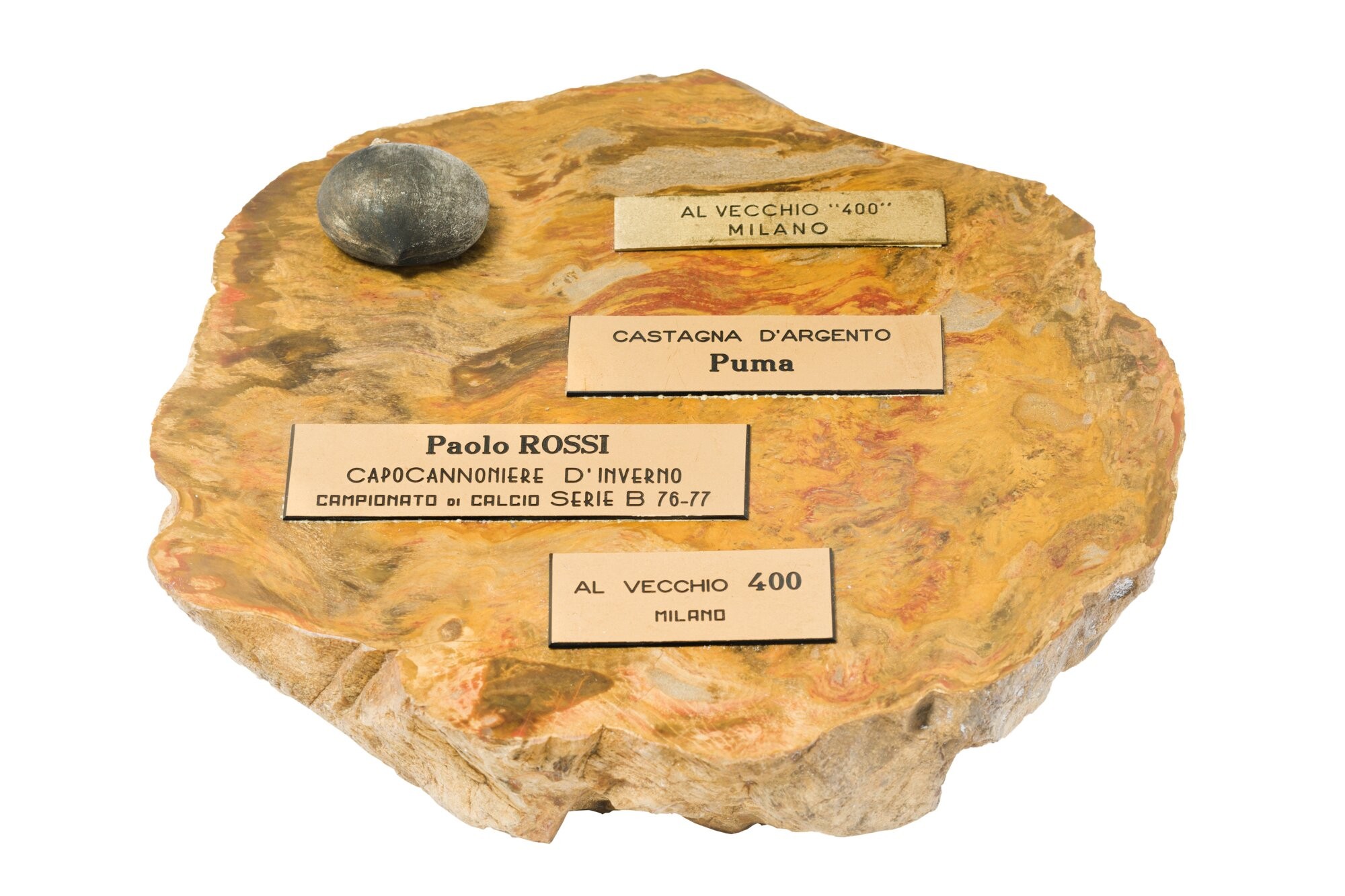

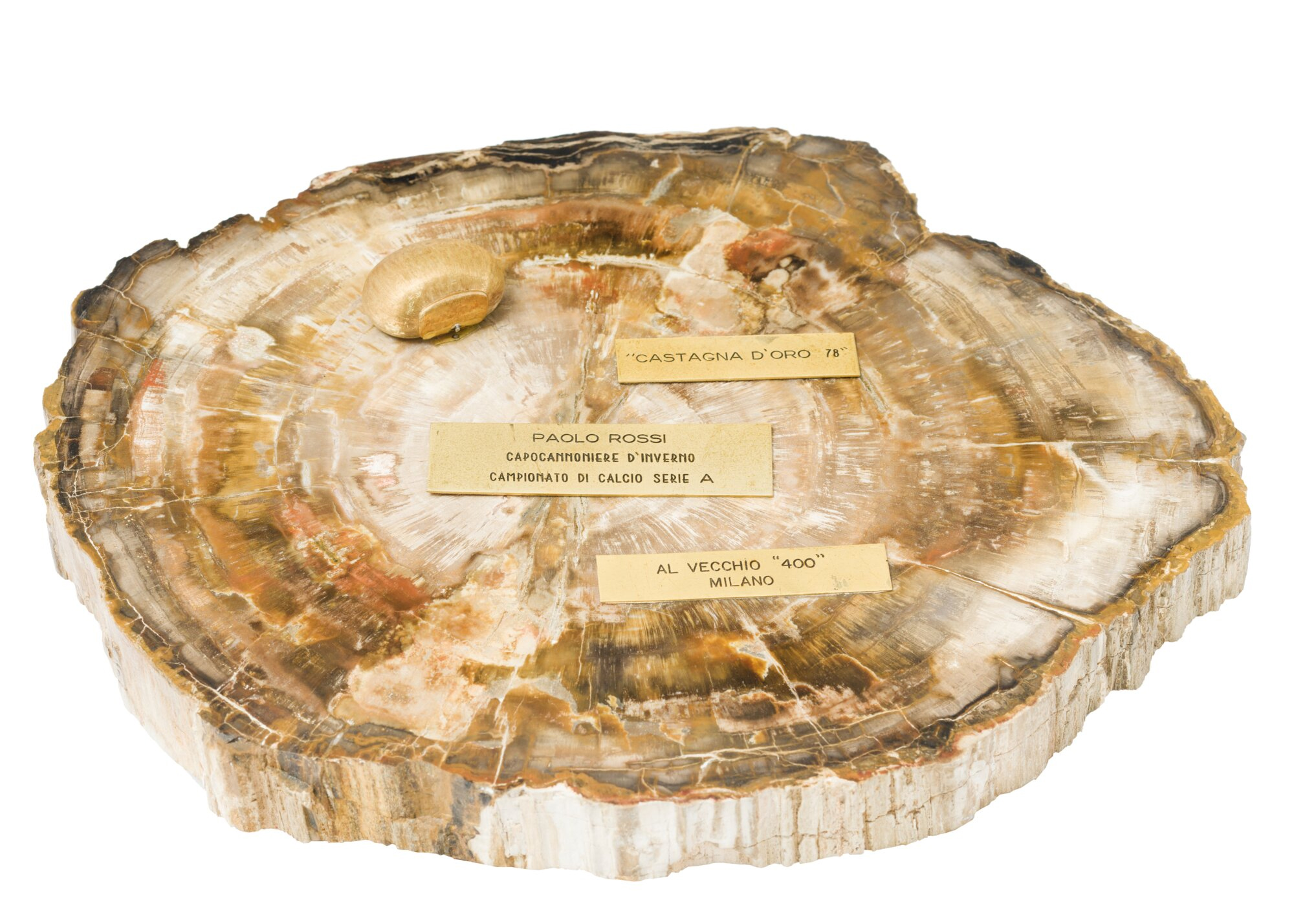

For Paolorossi, Vicenza is a new turning point. Not only does he play but, out of team necessity, coach Gibbi Fabbri takes away his winger’s jersey and gives him the number nine, making him a center forward. It’s a novelty for the boy from Prato, and at first, he doesn’t feel up to it—but soon his goal-scoring knack returns, and he finishes the Serie B season as top scorer, winning the Silver Chestnut award and leading Lanerossi straight into Serie A. This is also his military service period: postcards, a bersagliere’s cap, and an unlimited leave slip—all memories that last a lifetime. In 1977, he debuts Damasco with the military national team at the World Championship in Syria.

The following season, his already sky-high Serie B standards are repeated: Paolorossi is top scorer again and Vicenza finishes second, just behind Juventus. With this string of successes, it’s inevitable that Bearzot calls him up for Argentina 78. And though Paolino’s performance is extraordinary, we know that wasn’t yet his World Cup—even if it’s in Argentina that the boy born Paolo, known to all as Paolino, who grew up first as Paolo Rossi and then Paolorossi (all one word), officially becomes Pablito.

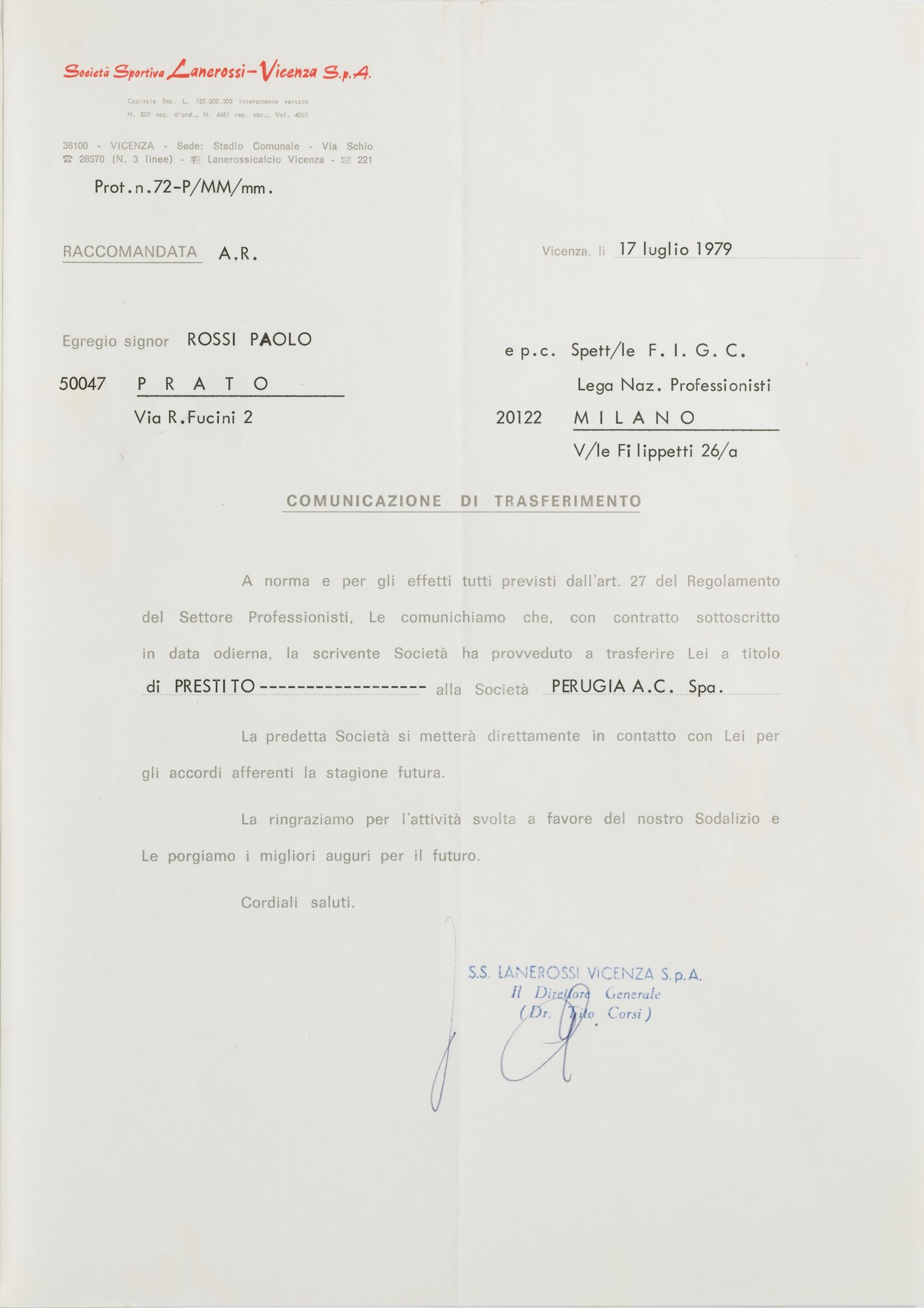

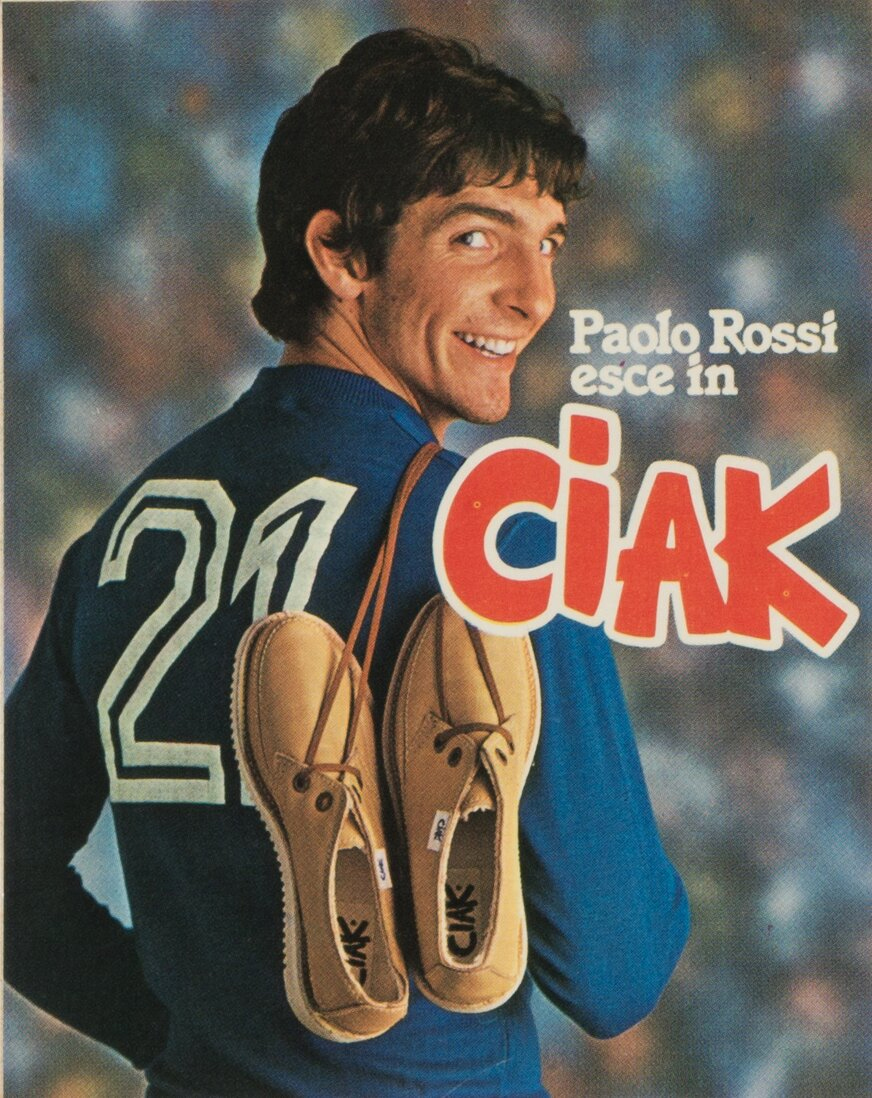

After Vicenza, Pablito is ready to set another milestone in football and sports history: in Perugia he becomes the first player to have a shirt sponsor. These are the years of trading cards and commercials, the years when Pablito is riding high, when girls fall for his shy smile, and everyone wonders how far this gentle boy’s career will go.

Yet, Paolorossi’s story seems written by a truly talented writers’ room—talented and ruthless. Because that’s how the best stories are written: with a pinch of cruelty toward the main character, since the greater the struggles they face, the more glorious the victory. At the end of 1979, he’s unwillingly caught up in a betting scandal, ensnared out of naivety, and ultimately handed a two-year ban. Two years’ suspension at twenty-three, when you’re the league’s rising star, is a tough pill to swallow. It means training with no prospect of playing, giving up goals, postponing the adrenaline of competition indefinitely; above all, it means the rest of the world moves on—the national team moves on—while he’s left watching, with no prospects, no more goals.

Luckily, Bearzot gives him one: he believes in his innocence—he always has—and promises to take him to Spain, to the 1982 World Cup, if he gets himself physically ready. Which means asking him to train with the same determination as someone who plays every Sunday. Will Pablito make it?

Rhetorical question: we, reading this, know exactly what he achieved.

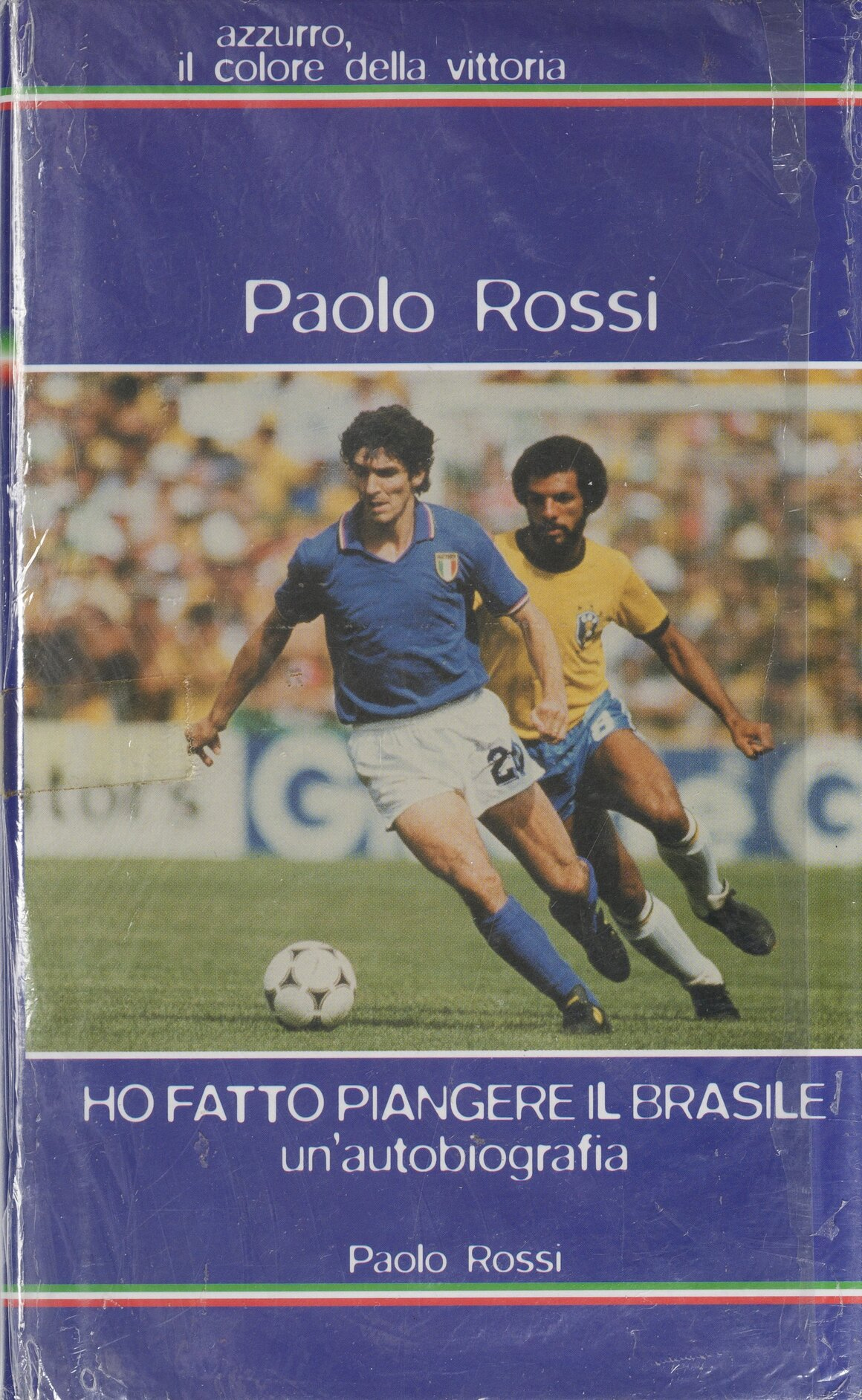

1982 was the year of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, the year of Thriller, the year of Commodore 64; it was the year Paolorossi laced up his boots again, donned the national team jersey, scored three goals against Brazil and then lifted the World Cupto the sky; the year he took the photo he wants to be remembered by; the year his first son, Alessandro, was born (Sofia Elena and Maria Vittoria would come later); the year he won the Ballon d’Or; It was the year Gabo won the Nobel Prize for Literature, the year of magical realism.

In fact, Paolorossi's story feels like it was written by Gabo.

Pablito hung up his shoes relatively early, a career cut short by knee and meniscus injuries. A short career, but in it he managed to win everything a footballer could dream of, both individually and with his teams.

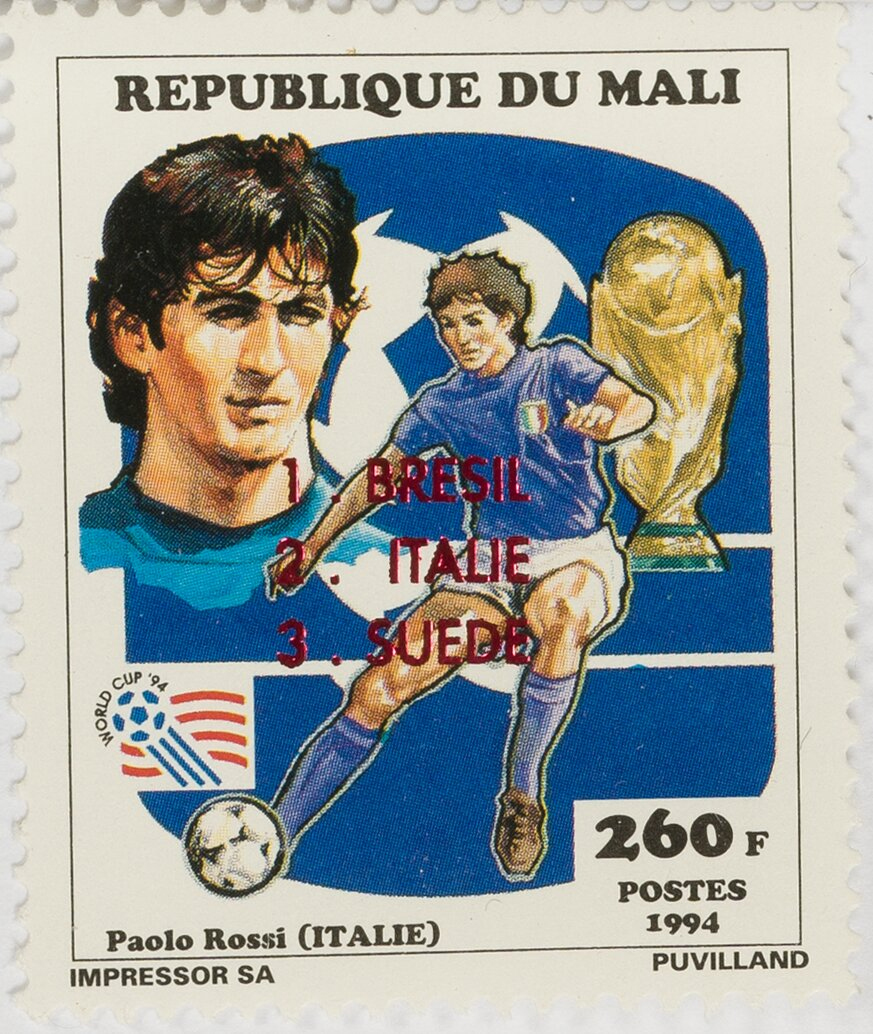

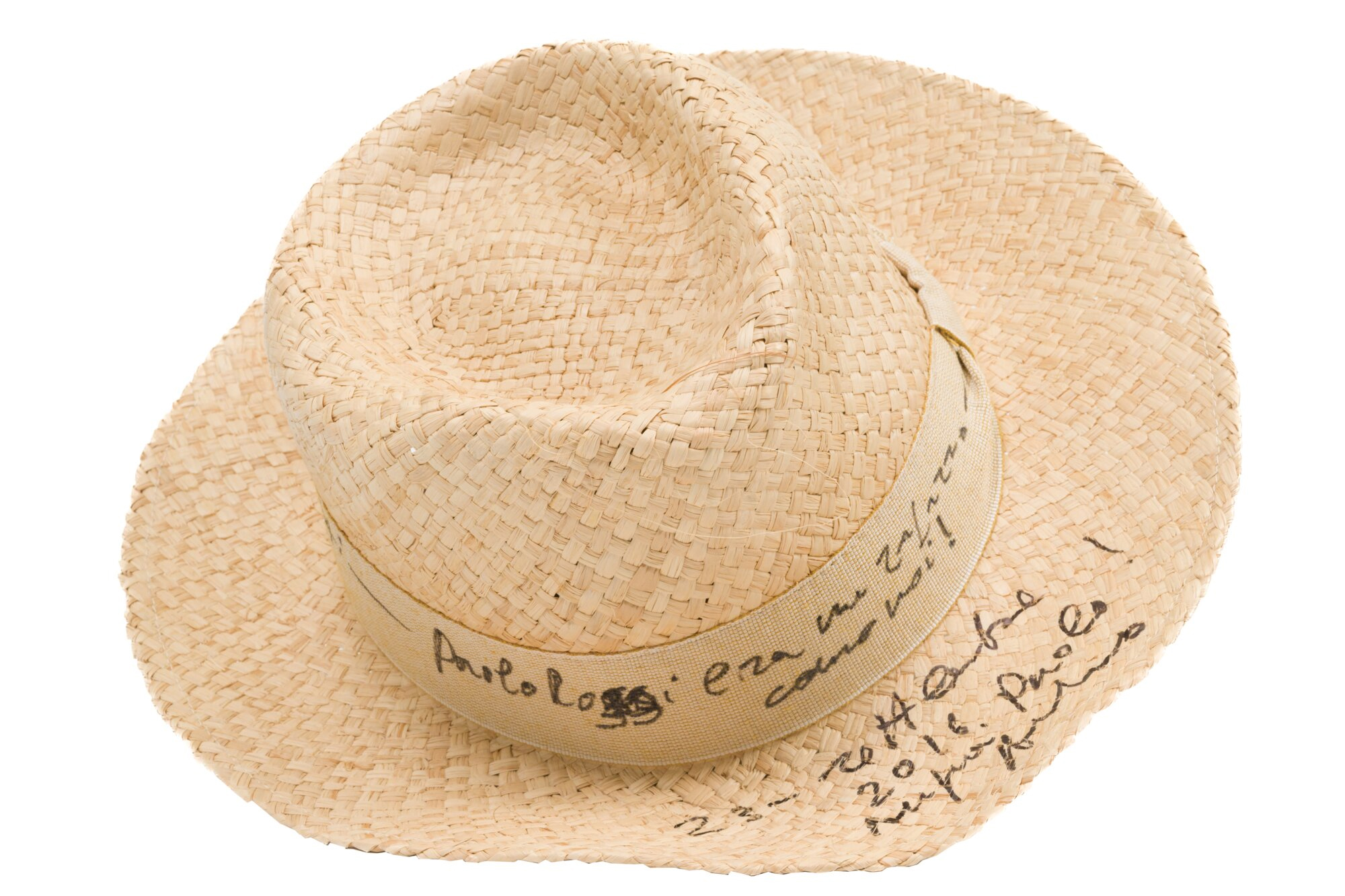

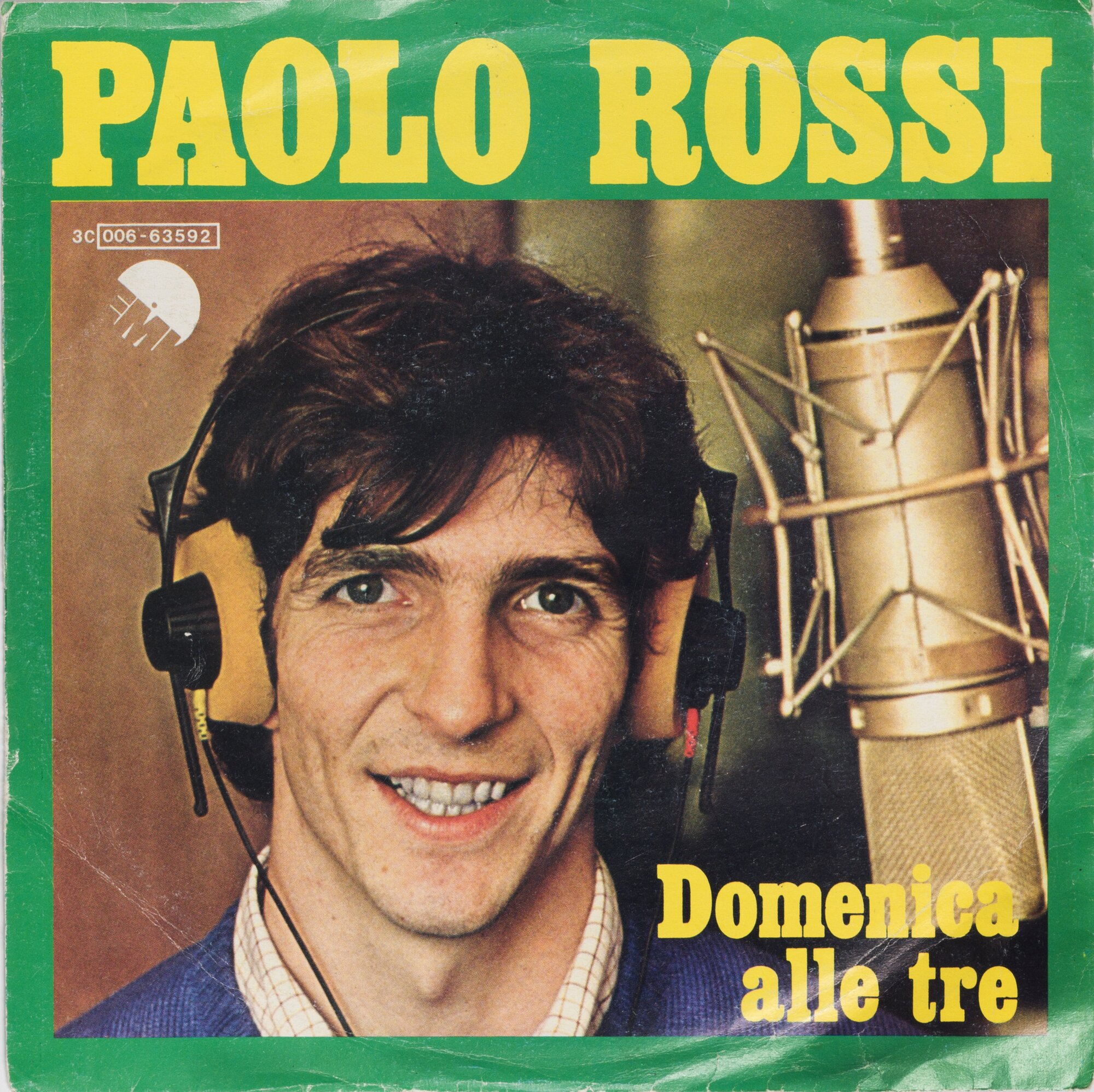

Above all, he won the eternal affection of fans everywhere, even the admiration of those he had made cry; the world dedicated to him a quantity and quality of postage stamps to make philatelists dizzy. Songs were written about him and with him. He had many friends and knew how to maintain sincere relationships with all, with the simplicity he learned on the dusty pitch of Santa Lucia, where the air smelled of olives and two stones were enough to make goalposts.

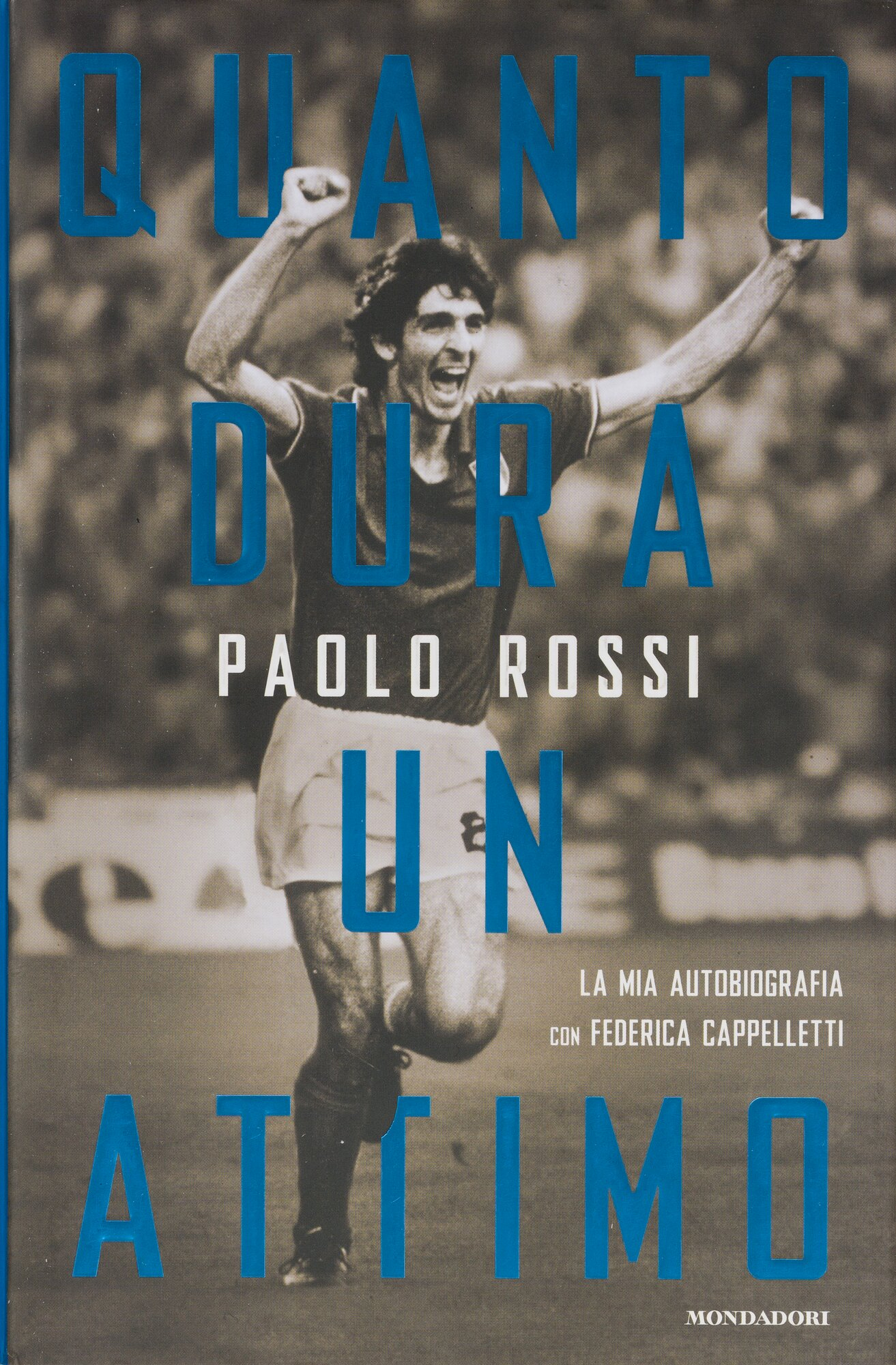

Much has been written about him, but the most intimate, personal biography is "HOW LONG A MOMENT LASTS", written with his wife, Federica Cappelletti. One day, over coffee, a memory resurfaced vividly in Pablito’s mind. Federica saw the spark, recognized the look of someone ready to tell his story from the very beginning, and they seized the moment.

If, instead of the ball…

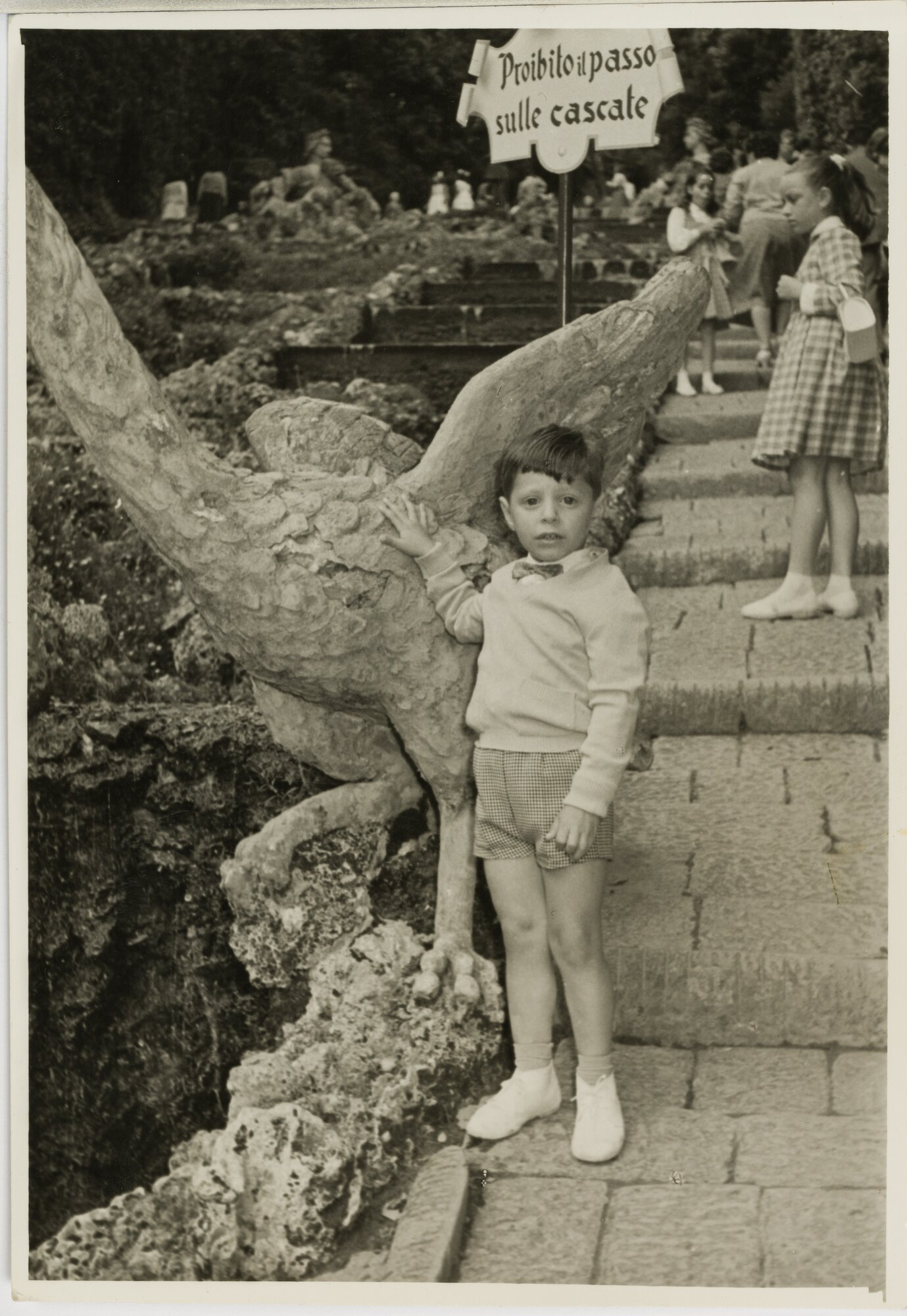

But the first time—the very first time—a ball rolled to the feet of a Paolino Rossi who hadn’t yet discovered his love for football, how did it go? Let’s picture him as a toddler, maybe a year old, maybe a little more? Barely able to stand on his own, and one Sunday, as the Rossi family heads to Mass, an improvised goalkeeper’s amazing save at the parish pitch sends the ball rolling onto the road leading to the churchyard. The ball does what balls do: it rolls. It rolls, and between the friction of the grass, a dog’s tail, and the clumsy touch of a late altar boy, it ends up in front of Paolino’s little feet, clad in Sunday sandals and white cotton socks.

“Go ahead,” says his dad Vittorio, kicking at the air to show him what to do.

Go on, echoes his brother Riccardo, who’s dying to kick the ball himself, but wants to enjoy his little brother’s first time.

Ball!” comes the call from the pitch.

“Come on, we’re going to be late,” says Amalia as the church bell rings.

And Paolino? What does Paolino do? He sizes it up, draws his little foot back, and—thunk—kicks the ball. The recoil, on just one tiny foot, knocks him onto his backside. But it doesn’t hurt—not at all. In fact, it’s the best feeling in the world, dancing with the ball. Of course, he’ll have to learn to control his kick, to stay on his feet after striking, to decide where to send the ball instead of finding out after the fact. Give him a few years, and he’ll do it all.

But what if, instead of falling in love with football, he’d fallen for something else?

If he’d loved the violin, he’d have been Niccolò Paganini.

If he’d loved mathematics, he’d have been Archimedes.

If he’d loved sailing, he’d have been Ferdinand Magellan.

If he’d loved sculpture, he’d have been Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

If he’d loved the guitar, he’d have been Francisco Tárrega.

If he’d loved the cinema, he’d have been Steven Spielberg.

But he loved football, and so he became Paolorossi.