“Imagine if, one day, Paolo Rossi walked onto the pitch from this underpass wearing the Perugia jersey.”

“It can be done.”

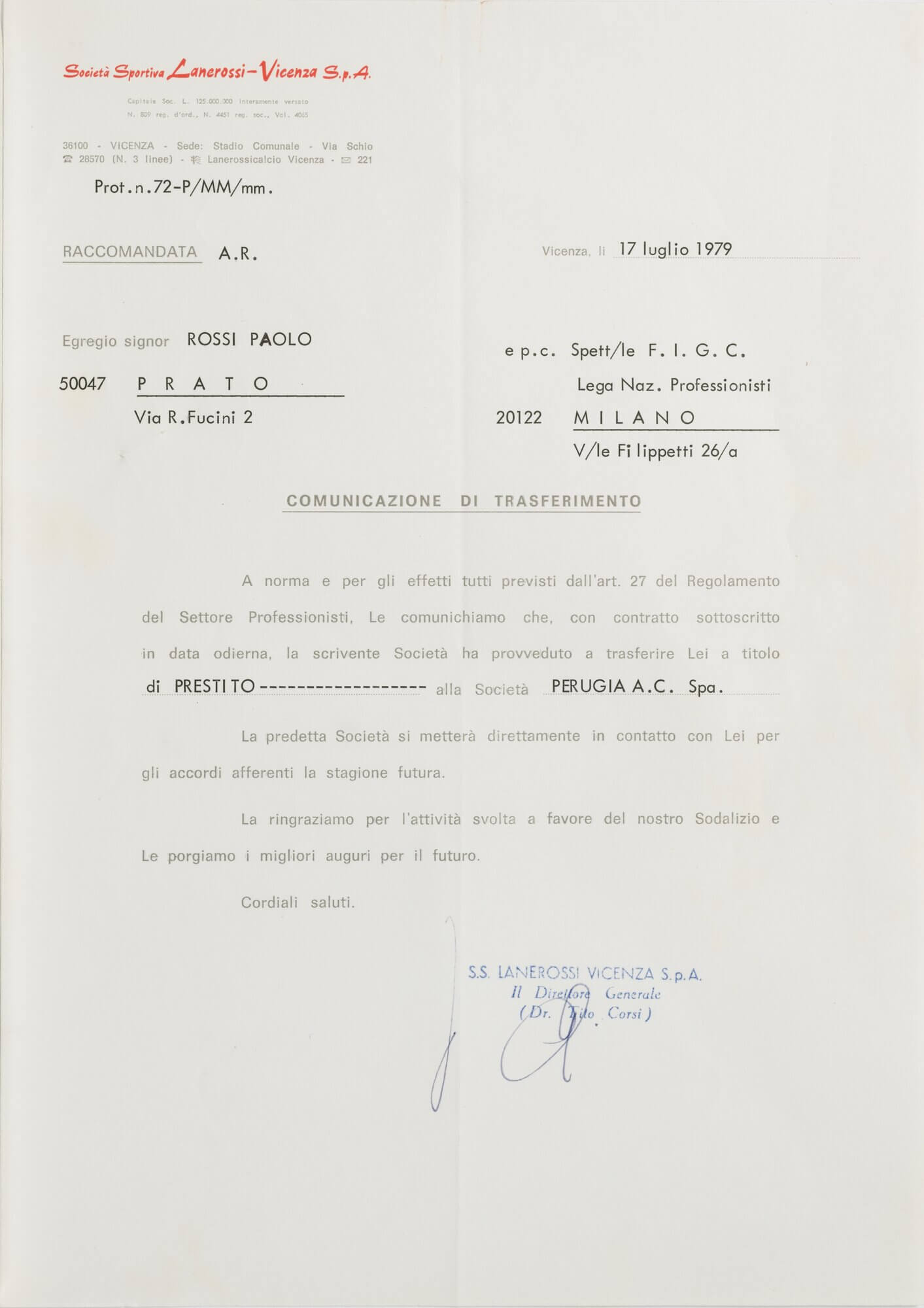

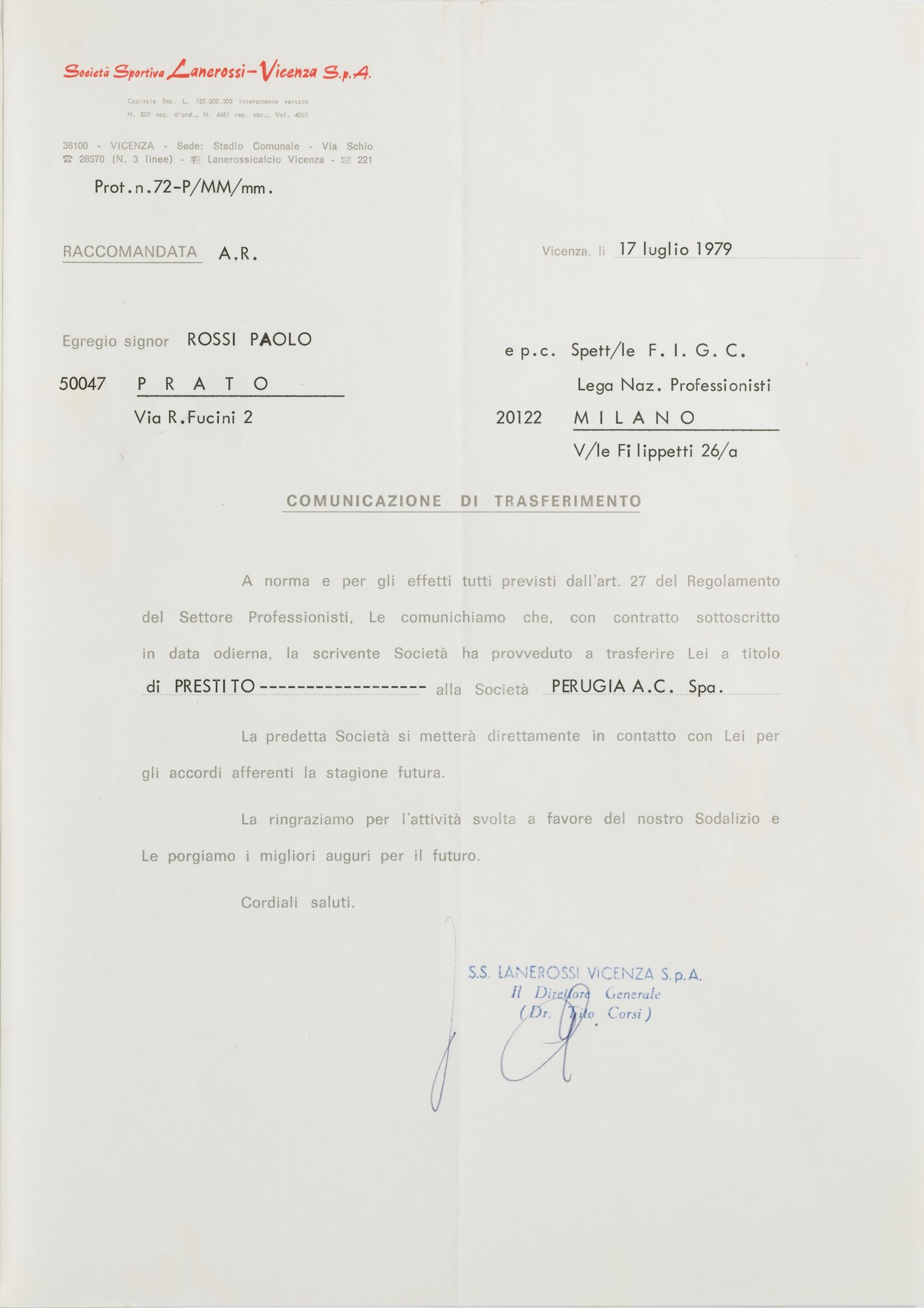

This dialogue, which sounds as if it belongs to that magical realism that would define the 1982 of Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Pablito, actually took place. It was the result of the vision of president Franco D’Attoma, the leader of the “Miracle Perugia”—the team that finished the 1978/79 Serie A season unbeaten, even if they didn’t win the Scudetto. The transfer market required big dreams, but Paolo Rossi cost a fortune. Yet, with a bit of imagination sometimes dreams come true. The key was in that “it can be done,” uttered by Gabriele Brustenghi, D’Attoma’s right-hand man at that very underpass. He was not only the president’s friend, but also the marketing director of Ellesse, the historic sportswear brand based in Perugia:

“I suggested to the president that we find a sponsor and put it on the jersey. I already knew who to pitch the idea to: the brothers Alfredo and Marino Mignini, owners of the Ponte di Perugia pasta factory in Ponte San Giovanni, in the province of Perugia. We had an excellent relationship, and they trusted me and D’Attoma. They gave us 400 million lire. That’s how shirt sponsorships were born in Italian football: to bring Paolo Rossi to Perugia.”

In the world of magical realism, though, things never happen in a straight line. “The Ponte sponsorship gave us the financial backing for the Rossi deal,” Brustenghi continues. “With Giussy Farina, the president of Vicenza, we struck a deal at his home in Versilia, but soon the problems started with the Federation.” Back then, in 1979, the jersey was seen as something sacred—at least in football. In tennis, however, Ellesse—whose president, Servadio, was D’Attoma’s brother-in-law—had already been putting its logo on players for years. The logo was already visible during Barazzutti’s Davis Cup triumphs and Chris Evert’s victories.

“When the idea started circulating, many people were scandalized. Inter’s president, Fraizzoli, said they’d have to walk over his dead body before putting a sponsor on the Nerazzurri shirt. A couple of years later, we saw the Fiorucci logo on that very jersey. Luckily, there were no dead bodies.”

The Ponte pasta factory, however, had to reinvent itself… as a sportswear brand! On Perugia’s jersey, beneath the Griffin, appeared the words “Ponte sportswear.” It was a trick to get around the rule that forbade sponsors unrelated to technical gear. “But they didn’t buy it,”, Brustenghi laughs. “The federation threatened fines and didn’t seem inclined to budge.”. Then came the moment to take the field. On August 26, 1979, Perugia emerged from the tunnel to face Roma in the Coppa Italia, with Paolo Rossi. The dream had come true, but with a twist: everyone came out of the underpass with the Ponte Sportswear sponsor. Paolo Rossi came out as well—but without the sponsor. The irony. Incredibly, the brand that had arrived mainly to help finance the signing of Pablito didn’t appear on the striker’s shirt. Rossi already had an exclusive one-year deal as a spokesperson with Polenghi Lombardo, another food company. Quite a problem, but the Magnini brothers didn’t back down. The sponsorship was an act of love for Perugia and a gesture of trust in D’Attoma—a man of integrity—who was forced to remove the logo after an initial 20-million-lire fine from the FIGC. Still, he pressed on, and on March 23, 1980, the Ponte Sportswear logo reappeared on all eleven Perugia shirts. And this time, Paolo Rossi wore it too. Yet, for the most attentive, that date rings a warning bell: it’s the day the police entered the locker rooms to arrest several players involved in an illegal betting scandal. Perugia was also implicated, because of an Avellino-Perugia match on December 30, 1979—a game in which Paolo Rossi scored twice. On March 23, Pablito wasn’t led away in handcuffs, but he would later be caught up in the trial and banned for two years. He always maintained his innocence, and the pain he endured is probably hard even to describe. But his redemption would come in Spain, 52 months later.